Murex trunculus shells and coins depicting them from the Roman period. Photo courtesy of Ptil Tekhelet.

JNS

KFAR ADUMIM, Israel—It was four decades ago that three childhood friends from New Jersey who had immigrated to Israel heard of a young Jerusalem rabbinical student who was looking for scuba divers who could help him find snails off the Mediterranean coast.

The three young men knew nothing about snails or the centuries-old search for the biblical blue known as tekhelet, but it was an adventure that would change their lives.

“It became a hobby that became an obsession that tuned into a mission,” Baruch Sterman, who took part in the sea outing 40 years ago, told JNS.

Sterman, 63, from Efrat, went on to co-found the Ptil Tekhelet nonprofit in this Jerusalem bedroom community on the road to the Dead Sea. It obtains snails to produce the biblical dye.

Ancient Mystery

The search for the source of the dye used for the biblical blue goes back centuries, and weaves together archaeology, chemistry and biblical scholarship involving chemists, marine biologists, a great Chasidic rabbi and a former chief rabbi of Israel who is the grandfather of the state’s current president.

For about 1,400 years following the Muslim conquest of the Land of Israel in the seventh century, the identity of the sea creature used to make the dye was lost to the world. This after two millennia when the purple and blue dyes derived from snails were used as a sign of royalty, coloring the robes of the kings and princes from Media and Babylon to Egypt to Greece.

Until that expedition four decades ago, no one wore the biblical blue on the fringes of their white prayer shawls other than a small group of Chasidim who followed the opinion of Rabbi Gershon Henoch Leiner (1839–1890), the first to be known as the Radzyner Rebbe, who thought he had found the source for the tekhelet from a squid, Sterman said.

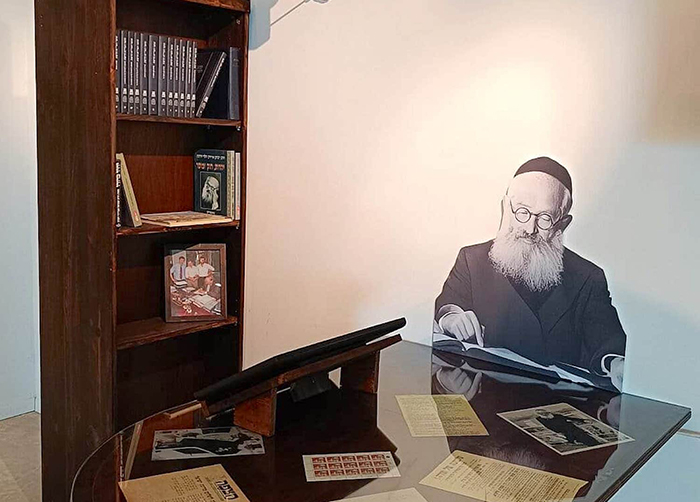

Rabbi Yitzhak Halevi Herzog, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the State of Israel, wrote a doctorate on tekhelet in 1913. Photo courtesy of Ptil Tekhelet.

But a 1913 University of London doctoral dissertation by the chief rabbi of Ireland, Rabbi Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog, who would go on to become the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Israel, and subsequent laboratory testing of material he sent for analysis found that the dye from the squid was inorganic and synthetic, a manufactured color created by the chemicals used in the labs and not by the sea creature.

For about two centuries, researchers continued to search for the source of the traditional biblical blue, a marine animal known, according to rabbinic literature, only as the hillazon.

A French zoologist found three mollusks in the Mediterranean Sea in 1858 that produced purple blue dyes, and identified one, the Murex trunculus (nowadays known as the Hexaplex trunculus), a medium-sized sea snail, as the source of the biblical blue, but they were not the pure blue described in ancient Jewish sources.

Researchers consulted at Washington’s Smithsonian Institution in 1979 also couldn’t figure out how to get the coveted sky blue from the sea creature.

Mystery Solved

The mystery was finally solved in 1985, when Prof. Otto Elsner at Israel’s Shenkar College of Fibers, who was researching ancient dyes, discovered that when exposed to sunlight, the snail’s dye was blue.

This led Eliyahu Tavger, the young Jerusalem rabbinical student, to enlist the three New Jersey men on their snail expedition on Israel’s northern coast.

“By the time we got there, we had fallen in love with the idea, having learned all the history in the drive up north,” Sterman, who had learned how to scuba dive during his student days at Columbia University, recalled.

They succeeded in taking a few hundred snails from the Mediterranean, producing five sets of tzizit, ritual fringes attached to the corners of Jewish prayer shawls. The snails produce tiny amounts of the coveted dye, requiring as many as 40 to color the fringe of one garment.

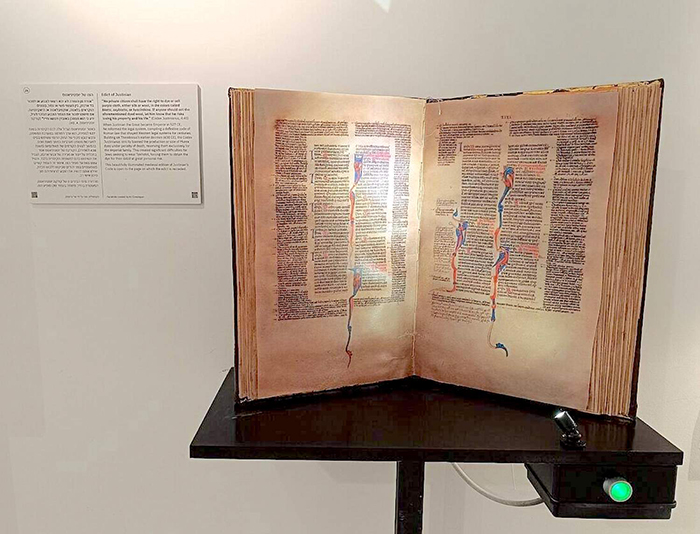

The sixth-century edict of Roman Emperor Justinian I, which made possession of tekhelet by commoners a capital offense. Photo courtesy of Ptil Tekhelet.

‘An Educational Mission’

Four decades and hundreds of thousands of Jewish prayer garments later, a small visitor center telling the story of the mystery of the biblical blue is being launched at the end of this month, at Ptil Tekhelet’s factory, located a 20-minute drive east of Jerusalem in the Judean Desert.

Protected Species In Israel

The enterprise, which was founded in 1991, sells cotton or wool Jewish prayer shawls with the biblical blue attached to one of the fringes, for about $50 each.

The snails used to make the dye are brought to Israel exclusively from abroad, including Europe and the Mediterranean countries, since they are a protected species in Israel.

The factory has already attracted Jewish and Christian tourists over the years, leading founders to press ahead with setting up an educational center at the site.

(A blue and white Israeli flag with the biblical dye used in the factory was presented to U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during President Donald Trump’s first term in office.)

The visitor’s center tells the story of tekhelet from ancient times to the present and its rediscovery, along with a view of the dyeing process. “We felt it was not just a goal to provide tekhelet for people who want to wear it,” Sterman said. “We believe that this is an incredibly inspirational story bringing together science, Torah, spirituality and our culture all wrapped together.”