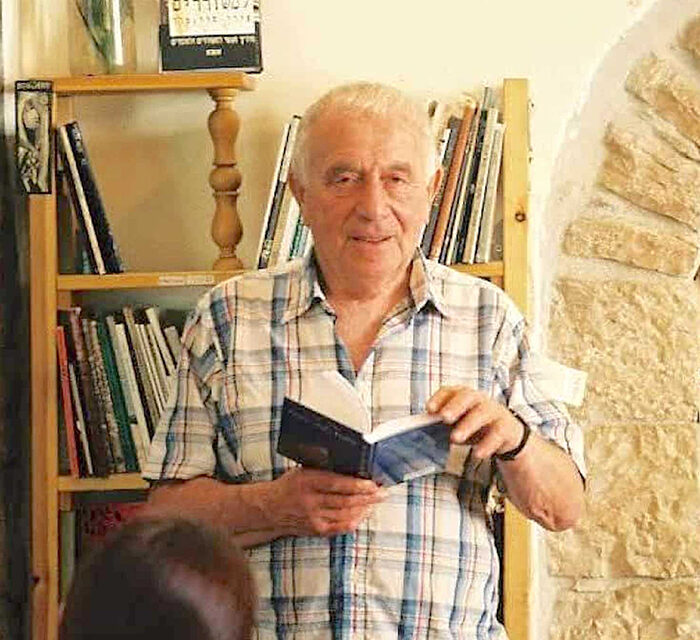

The late Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai.

By JULIANA GERAN PILON

JNS

The virulence and ubiquity of left-wing anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism after the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel stunned American Jews. Campuses, most spectacularly the Ivies, let loose mobs of Islamist sympathizers cheering for the thugs who had just killed hundreds of dancing young people and butchered whole families in their beds. They slandered the “occupiers” as “colonialist imperialists,” demanded the end of Israel and denounced America’s alleged “complicity.”

Fear And Astonishment

The establishment press outside of Israel meanwhile often referred to the terrorists as “militants,” even as video footage of the slaughter went viral on social media around the world. The satanic butchers were applauded by cheerleaders across the United States, the United States, a place that jihadists contemptuously call “Big Satan.” Nazi-style graffiti, threats against synagogues, attacks on yeshiva students—all contributed to an unprecedented sense of insecurity among American Jews. Months later, it continues.

Not that most ordinary people didn’t immediately sympathize with the Israelis. But Jews could not go on ignoring mainstream progressive ideology, which had politicized victimhood by demonizing “white racist oppressors.”

Suddenly An Enemy

Jews had originally signed on to the leftist narrative that claimed to favor underprivileged victims of the wealthy and powerful because compassion is central to the Jewish tradition. Besides, having unwillingly won first prize in the lottery of persecution, they felt they had a duty to sympathize with the less fortunate.

But forgetting their precarious status as a tiny ethno-religious minority whose outsized economic and social success had become politically inconvenient, it shocked American Jews to realize that they had been relegated to enemy status. Used to fearing only “the right,” hardly any remembered, or wanted to know, the role of Karl Marx’s question about the Jew: “What is his worldly God? Money,” making capitalism and Judaism interchangeable. On the left, anti-Semitism as anti-Capitalism had always been a feature, not a bug.

Who Can Help?

Most American Jews have traditionally placed their bets on the educated elites, read The New York Times and sent their kids to the “best” schools. They supported Israel knowing it to be by far the freest country in the Middle East and America’s most steadfast ally. And now what? Where to look for guidance?

Then I discovered Yehuda Amichai.

Though he died in 2000, British-born Harvard professor James Wood, literary critic for The New Yorker, declared in 2015 that Amichai “is still Israel’s most celebrated poet.” He sought to make his poetry “useful” and accessible to ordinary people and thus he is loved far and wide. With their copious references to biblical passages, “his poems have been called the nation’s ‘secular prayers,’” writes Wood. “He is quoted at funerals and weddings, in political speeches and ceremonies, in rabbinical sermons and in a Jewish American prayer book.” He became a kind of secular cantor.

Born in Würzburg, Germany in 1924 to an Orthodox Jewish family, Amichai was raised speaking both Hebrew and German. His family fled Nazism in 1935 and arrived in Jerusalem in 1936. He fought in World War II as a volunteer and then in Israel’s subsequent wars, but still managed to write 11 volumes of poetry in Hebrew, two novels and a book of short stories. Recipient of the 1982 Israel Prize for Poetry, his work has been translated into 37 languages.

Elusive Peace

Amichai’s Orthodox upbringing notwithstanding, he was ecumenical. Always a maverick, he liked to rebel against all authority, religious or secular. Well, at least a little. “Amichai is a man who, as he once playfully put it, rebelled only a little, because he did, after all, observe the laws and the commandments—the laws, he quickly adds, of gravity and equilibrium, and the horror of the vacuum,” writes Wood. “Which is to say, he belongs not only to Israel and to the Hebrew language but to all of us.” As does Israel itself belong to all of us.

And there it was, a poem that Amichai penned exactly three decades ago, in December 1994, tailor made for today, especially in the aftermath of Oct. 7. Its theme is universal and timeless: the never-ending desire for peace.

Wildpeace

Not the peace of a ceasefire

not even the vision of the wolf and the lamb,

but rather

as in the heart when the excitement is over

and you can talk only about a great weariness.

I know that I know how to kill, that makes me an adult.

And my son plays with a toy gun that knows

how to open and close its eyes and say mama.

A peace

without the big noise of beating swords into plowshares,

without words, without

the thud of the heavy rubber stamp: let it be

light, floating, like lazy white foam.

A little rest for the wounds—who speaks of healing?

(And the howl of the orphans is passed from one generation

to the next, as in a relay race:

the baton never falls.)

Let it come

like wildflowers,

suddenly, because the field

must have it: wildpeace.

Giving Up?

“Not the peace of a cease-fire,” for that only gives the killers a chance to rearm. “Not even the vision of the wolf and the lamb,” soothing as it may seem. For we cannot realistically hope for “a peace without the big noise of beating swords into plowshares.” Swords are still necessary. The kind of peace he has in mind is rather a feeling “in the heart when the excitement is over and you can talk only about a great weariness.” Not pleasure, but the sort of relief that comes from the weariness of trying to survive, after the awful excitement of fighting herculean odds. The weariness of almost losing hope, of almost giving up. But giving up is never an option. So it is written and so it must be. L’chaim. You always have to be prepared to defend life—your own and the lives of your loved ones.

“I know that I know how to kill, that makes me an adult.” That terrible knowledge is merely necessary; it can never be sufficient. A psychopath who knows how to kill is no adult; he is not even human in the true, rather than merely biological, sense of the word. To be an adult, you also have to know that killing is wrong except when you are obliged to protect yourself and those you love. The raw mechanics of knowing how to use a gun is child’s play; even “my son plays with a toy gun that knows how to open and close its eyes and say mama.” To be an adult, I must be prepared to lose my own life to protect my son.

If only it were possible never to have to kill anyone. How would it feel not to be afraid again? To “learn war no more,” as the flower children used to sing in the ’60s? “A peace without words” is like music that can lubricate terminal sorrow with the voice of love. Not what Vietnam-era antiwar activists who chanted “Make Love Not War” but went on to lionize Soviet-armed Viet Cong guerillas, mass-murderer Mao and hardcore criminal Che Guevara had in mind. The abolition of difference, the canceling of strife, cannot be imposed but must emerge from within the soul, “without the thud of the heavy rubber stamp.” The consensus of state-enforced groupthink, with dissent crushed beneath the policeman’s boot, is a death in life, an insult to man and God.

Healing?

Peace should be like a candle’s blessing: “Let it be light, floating, like lazy white foam” imagines the poet. Someday, military action will succeed in Gaza and even the Iranian octopus with its deadly terror tentacles may eventually be defeated, assuming the cancer has not already spread too far. But at least we can hope for “a little rest for the wounds—who speaks of healing?”

Healing might never be possible. The raw pain of the deaths of Oct. 7 will not go away. We will not let it disappear. As so often throughout history, “The howl of the orphans is passed from one generation to the next, as in a relay race: the baton never falls.” Now and forever, Jews will carry the baton. Israelis’ resolve has been immeasurably strengthened; illusions unmasked, they are recalibrating strategies. Will diaspora Jews realize that it’s their baton too?

The poet ends on a note of hope: We must believe that peace will come eventually. “Let it come like wildflowers, suddenly.” It will come, he tells us, “because the field must have it.” What a lovely name: “wildpeace.” “Shlom bar”: the peace of fields. It is the peace of God-given life.

Bible Symbols

As Amichai’s poem necessarily reflects the Torah, it helps to be familiar with the Torah’s wisdom. I must confess that having been born in communist, atheist Romania, where Hebrew was outlawed, I had a lot of learning to do after emigrating to the U.S. Luckily, I had recently joined a small group of mostly religiously self-educated University of Chicago alumni, eager to apply old wisdom to the present by sharing personal interpretations of exodus. And as it happened, Oct. 7 came after we talked about Amalek. It helped us to process the enormity of what had just happened.

The nomadic tribe of Amalek symbolizes the arch-rival of ancient Israel. In Exodus, the Amalekites are said to have attacked the Israelites unprovoked as they escaped from slavery in Egypt to return to the land of their ancestors. Though Israel was able to defeat them, and the Amalekite nation itself no longer exists, its symbol as Israel’s devious, evil enemy has persisted.

Amalek’s jihadist brood will not be easily defeated, as the dead and wounded IDF soldiers—and indeed the defenseless Palestinians whom terrorists keep as shields and cannon fodder—testify for all the world to see; should it choose to see. Until Amalek’s latest incarnation is slain again, the world is in grave danger and the field-flowers cannot bloom. It will be slain because it must be. But we cannot allow ourselves to become complacent again.

This is an edited version of an article originally published by The New English Review. Juliana Geran Pilon is a senior fellow at the Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization. Her latest book is An Idea Betrayed: Jews, Liberalism, and the American Left (2023). She has taught at the National Defense University, the Institute of World Politics, American University, St. Mary’s College of Maryland and George Washington University.