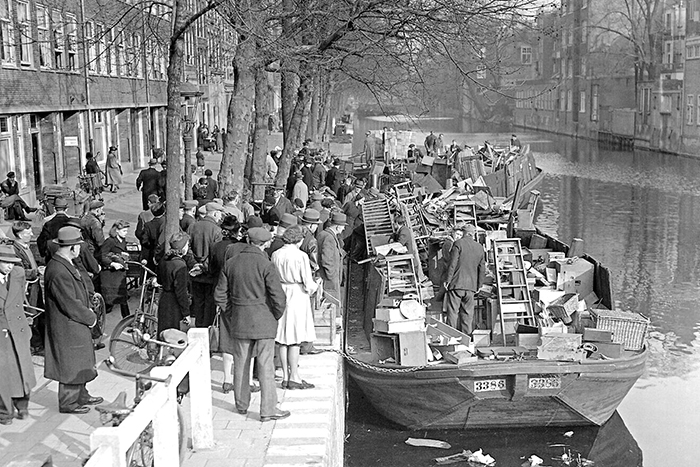

Stolen household goods from deported Jewish inhabitants. Amsterdam, March 18, 1943. Photo courtesy of National Archives/Collection Spaarnestad/ANP/Daan Noske. | National Archives/Collection Spaarnestad/ANP/Daan Noske

JNS

Stories about art looted during the Holocaust abound, but they tend to focus on major works by noted artists worth vast amounts of money.

“Beyond the masterpieces, there remains a largely hidden world of lesser-known looted items, from household goods that belonged to deported Jewish neighbors to objects from Jewish places of worship, community buildings and private libraries and archives,” according to the catalog accompanying the exhibition “Looted” (through Oct. 27) at the Jewish Museum and the National Holocaust Museum in Amsterdam.

The exhibit and catalogue, “Dispossessed: Personal Stories of Nazi-Looted Jewish Cultural Property and Postwar Restitution,” are co-productions of Amsterdam’s Jewish Cultural Quarter and the Rijksmuseum, which is more than 225 years old, and among the world’s most visited and largest museums.

Eight Lost Collections

The show traces the stories of eight collections the Nazis seized: Leo Isaac Lessmann (Judaica), Franz Oppenheimer and Margarethe Oppenheimer– (Meissen porcelain), Albert Heppner and Irene Marianne Heppner– Krämer (paintings), the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana (books), illustrator M.C. Escher’s teacher Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (art), Louis Lamm (books), Dési Goudstikker (widow of art collector Jacques Goudstikker) and Margarete Stern-Lippmann (art).

In the instance of the Heppners, who were German-Jewish refugees, the couple’s then-7-year-old son Max saw officials confiscate his parents’ collection. “I witnessed the theft with my own frightened eyes, even though I didn’t really know about everything that was at issue,” he said, per the catalogue. “All I knew was that my family’s space was being invaded and our family’s possessions were being stolen. Of course, later I learned that the Nazis also were scheming to take our lives.”

Help?

When German troops entered Amsterdam in May 1940, the Heppners tried in vain to flush “incriminating” documents down the toilet or to burn them on the stove. “In the end, they sank a pile of anti-Nazi magazines in a nearby canal,” per the catalogue. “Around sunset, on their way back home, they saw many little fires burning elsewhere in their neighborhood,” adding that “anxious” neighbors were, like they, “harmoniously burning together the contraband.”

The collectors’ non-Jewish family doctor refused to bury their jewelry in his garden. “Our doctor was a good friend of the family. My mother trusted him fully. But when we were in need, he didn’t help us,” Max said, according to the catalogue. “He said he wanted to comply with the new regime, and he thought it wise for everyone to do the same.”

‘Made two needs possible’

“Chillingly,” the catalogue adds, the doctor offered the Heppners poison, “because he suspected that things would not end well for the family.” Instead, they found others to hide their belongings. “A friend took charge of two of their silver candlesticks, on condition that she would not be expected to polish them. A washerwoman also helped to spirit some of their things away,” the catalogue records. “According to Max: ‘Each time she came to collect our laundry, she would hide things in it that she would then keep safe at her home. At the end of the war, every single thing was given back—and that was by no means always the case.’”

Mara Lagerweij, a provenance researcher at the Rijksmuseum and curator of the exhibition, told JNS that the museum “has been conducting World War II provenance research since 2012.” (Provenance is the history of an object’s ownership.)

“This involves looking at all acquisitions from 1933 onwards,” Lagerweij told JNS. “Currently, these reports are also being translated into English. Next year, a report will also be published on donations to the museum from German Jews who fled the country (Germany), often while simultaneously applying for Dutch citizenship.”

The collaboration between the Rijksmuseum and the Jewish Cultural Quarter “made two needs possible,” according to Lagerweij, “to make an exhibition on both art and Judaica and to work with historical locations.”

“Jewish Museum is a historical location from which the looting of books and Judaica took place,” she said. “National Holocaust Museum is a historical location where you can put looting in the context of the Holocaust (and) dehumanization.”

The catalogue and the exhibit have a lot to say about what it means to people to be stripped of their prized possessions.

‘Part Of Dutch History’

“The organized, systematic theft of property was one component of the process of the dehumanization of Jews during the Second World War that culminated with the Holocaust,” according to the catalog.

“Now that almost no survivors of the Holocaust remain, it is ever more important to keep telling the story of what happened to them,” it adds. “The Jewish Cultural Quarter and the Rijksmuseum are therefore committed to reconstructing and telling the stories of theft, confiscation or loss of property under duress from the Nazi regime, in order to perpetuate them as part of the Dutch history of the Holocaust.”

“For many years, the Netherlands remained stuck in the conceptual dichotomy of the right or wrong side in the war, and lived under the illusion that most of the Dutch had been involved in resisting the Nazi occupation,” added Emile Schrijver, general director of the Jewish Cultural Quarter, in the catalogue.

“Acknowledging the many shades of gray between black and white was a taboo that it took decades to overcome,” Schrijver added. “Evidently, only the passage of time made it possible to face uncomfortable truths.”