By MARILYN SHAPIRO

For newlyweds Erwin and Selma Diwald, getting out of Austria wasn’t a choice. It was a necessity.

Their daughter, Frances “Francie” Mendelsohn, recently shared their story with me.

A Comfortable Life

Despite the undertones of anti-Semitism and the looming threats coming from Hitler’s rise in Germany, the two who would become her parents, were two young Jews living comfortable, family-centered lives in the beautiful city of Vienna prior to their meeting at a cousin’s wedding in 1936.

Bettina and Sigmund Diwald had welcomed their first child, Erwin, in 1907. Eighteen months later, a daughter, Paula, was born. Sigmund ran a successful business in which he imported ostrich and egret feathers used in the making of hats popular at that time. There were slights because of their religion: When he was 14, Erwin was allowed to be part of a four-piece string quartet under the condition that he play his violin in the foyer during practice. Upon graduation from high school, Erwin attended the University of Vienna, where he earned doctorates in both history and law. He launched a successful career in law and was sought after by many Catholic clients wishing to legally annul their marriages.

Born in 1912, Selma was the eldest child of Maria and Victor Gehler and older sister to a brother Joel. Victor, an engineer, was involved in the building of the Wiener Riesenrad Ferris wheel in the Wurstelprater (also known as Prater), an amusement park that is still considered one of Vienna’s more popular tourist attractions. Selma worked in her uncle Simon’s drugstore while attending the University of Vienna’s pharmacy program, intending to step into her uncle’s business after graduation.

Planning A Life

Both were looking forward to their lives together in Vienna when they married in October 1937.

Six months later, German troops invaded Austria. On March 15, 1938, the terrified Erwin found himself caught up in the enthusiastic crowds cheering and raising hands in the Nazi salute as a triumphant Hitler paraded through the streets of Vienna. Immediately, the Jews in Austria were in the crosshairs of the new regime.

Getting Out Of Dodge

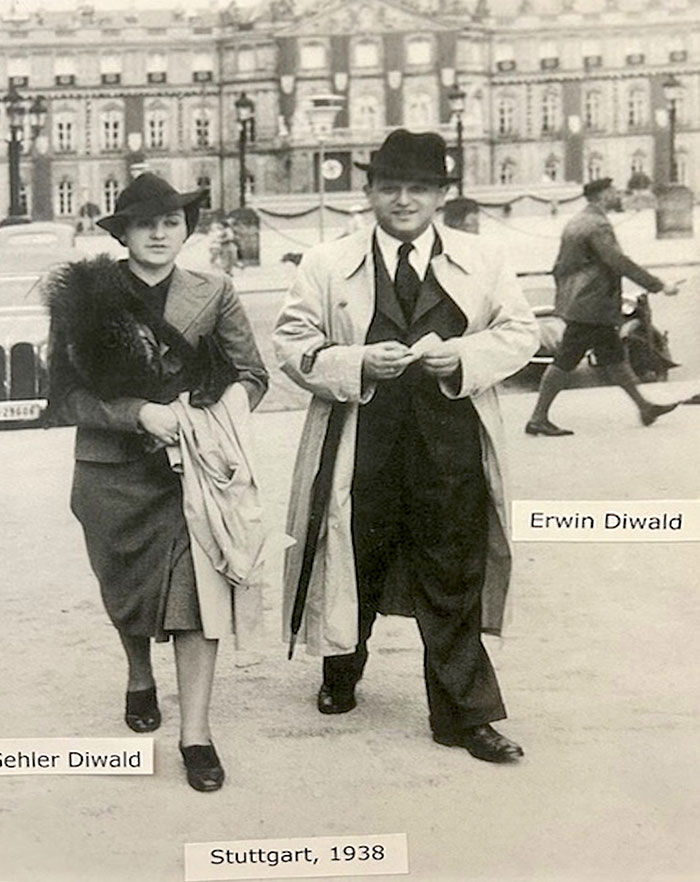

The newlyweds decided to find refuge in the United States, a challenge compounded by their lack of any American ties. Their first attempt to obtain visas took them to Stuttgart, Germany. On their first evening in the Hotel Silber, Selma and Erwin sat down for dinner in the hotel’s restaurant. The waiter brought over a huge tureen of soup. “Compliments of the fuhrer,” they were told. They soon learned that their hotel was the site of the Gestapo’s regional headquarters. The next morning, they checked out and returned to Vienna to explore safer options.

Help arrived through Erwin’s younger sister. Paula Diwald had been vocal in her dislike for the new regime. When notified that the Nazis were looking for her, she hastily made arrangements for a “ski trip” in France. As soon as she crossed the border, she ditched the skis and took up residence in Paris. Paula worked during the day as a salesclerk in a shop selling expensive handbags. To supplement her income, she worked as a tour guide; her ability to speak seven languages was a definite asset.

A Favor

One evening, Paula introduced herself to a couple requesting a guide who could speak English. She spent the next several days showing the Gregorys from Chicago, Ill., the highlights of the City of Light. At the end of their visit, they asked Paula what they could do to thank her for all that she had done.

“What you can do is sponsor my brother and his wife,” Paula told them. “We have absolutely no family in the United States. Your providing them with visas is the only payment I want.” They promised to see if they could make the arrangements once they returned to Chicago.

The Greek Connection

Paula immediately contacted Erwin. His education had included years studying classical Latin and Greek, and he decided to use this knowledge to further persuade the couple, members of a Greek Orthodox Church in Chicago. He wrote a long eloquent letter to them in classical Greek to plead his case.

The Gregorys may have been Greek Orthodox but they had no knowledge of the Greek language; they brought the letter to their priest. Impressed by both the Erwin’s language and moved by his plight, the priest told the Gregorys, “You have to save these people.” The Americans complied and began the process of getting visa for the couple. They enlisted the aid of Lazarus Krinsley, a Jewish lawyer from Chicago, to obtain the paperwork.

The Diwalds flew to Paris to await the paperwork. Repeatedly, the official responsible for their case said that the visas had not come through. After weeks of disappointment, the Diwalds checked in on a day that another person was covering for the absent official. “Where have you been?” said the substitute. “These visas have been here for months!”

Sea Voyage

The Diwalds arranged first -class passage on the Paquebot Champlain. Built in 1932 and hailed as the first modern liner, the ship had been pressed into evacuee work, transporting many Jews, like the Diwalds, who were fleeing Europe.

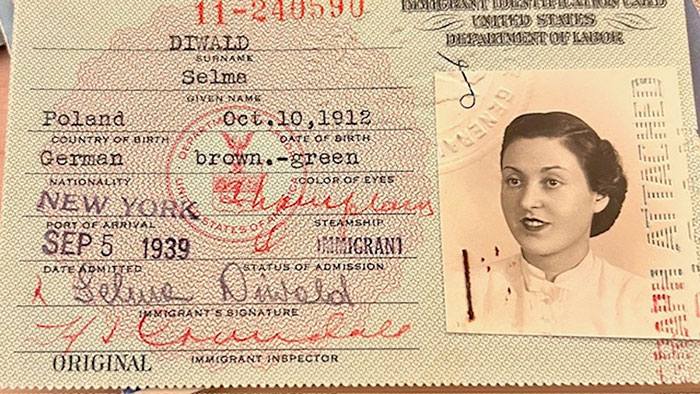

Erwin remained in Paris with Paula before boarding the ship in Le Havre, France, on Aug. 29, 1938. Later that day, Selma, who had gone to England to say goodbye to her family, boarded in Southhampton. On Sept. 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, marking the beginning of World War II. Erwin and Selma had made their escape just in time. The ship sailed in radio silence for the remainder of the voyage.

During their ocean journey, the Diwalds found themselves in the company of celebrities who were also leaving Europe amid the rising tensions. Their travel mates included actor Helen Hayes, comedian Groucho Marx, composer Samuel Barber, Italian-American composer Gian Carlo Menotti, and Austrian-American actor/director Erich von Stroheim. The newlyweds enjoyed a memorable, if not bittersweet, voyage!

A New Life

After debarking the ship in New York City, Selma and Erwin traveled to Chicago to meet their benefactors. Even though the Gregorys were responsible for getting the visas, they were not welcoming. Their lawyer Lazarus Krinsley and his wife Rose, however, warmly embraced the couple, establishing a lifetime friendship. Upon the Krinsleys’ recommendation, the Diwalds settled in Milwaukee, Wisc., which had a fairly large Jewish population and offered job opportunities.

Because his law degree was from an Austrian university, Erwin was unable to practice law in the United States. During the war, he worked on an assembly line that polished propellers for B-59 and drove trucks. After the war, Erwin applied for a job as a tire salesman with Dayton Tire and Rubber Company. Initially, personnel in Human Resources failed to recommend him, saying he was “too intelligent.” Hired despite the negative review, Erwin went on to become one of their top salesmen.

Using the skills she had learned in Vienna, Selma worked in a pharmacy. She considered going to UW Madison to get certified as a pharmacist. After the birth of her two daughters Ann Frances [“Francie”) and Susan Jane, however, she gave up her dreams of further education.

The Diwald family joined to Temple Emanuel, a Reform congregation. In 1954, Francie became the first bat mitzvah in the congregation, with her sister having one three years later.

Story Seldom Told

Erwin and Selma shared little of their Holocaust story with children Frances and Susan. Frances said that the first time Erwin opened up was when Frances brought home her future husband Eric. “I listened in amazement as my father gave Eric a detailed account of their flight from Vienna, Austria, to Milwaukee, Wisc.”

Fortunately, many other members of Selma and Erwin’s extended family were able to escape from the horrors of the Final Solution. In 1938, the Nazis stormed into the Gehler home looking for Joel. When they could not find him, they arrested Selma’s father, Victor, who was deported to Dachau. Maria, through what Frances speculates may have been a sizable bribe, paid off SS officials to free him. They immediately fled for Haifa, in what was then called Palestine, and lived there until their deaths in 1951, three years after celebrating the establishment as the State of Israel.

Erwin’s parents had also escaped Austria in the summer of 1940 by hiking over the Alps into France. They immigrated to Milwaukee in 1942. Joel, who had narrowly missed arrest in 1938, fled to England. He settled in London, eventually marrying Patricia, “the love of his life.” Joel passed away in 1986; Patricia passed away in 2022. Paula remained in Paris, eventually marrying and settling with her husband in south France.

Selma died in 1996 at the age of 83 from cancer. Erwin died in 2008 at the age of 101, suffering from dementia in his last years. Despite what the family had endured, Frances Mendelsohn said that her parents were never bitter or angry.

“I feel as if I been touched by God,” Erwin told his children. “We survived.”

*An interesting note: According to a Wikipedia article, the Champlain was built in 1932 and hailed as the first modern liner. After war was declared, the ship continued crossing the Atlantic Ocean, transporting refugees, including many Jews, to safety. On June 17, 1940, on what was to be its last crossing, the Champlain hit a German air-laid mine, causing it to keel over on its side and killing 12 people.. A German torpedo finished its destruction a few days later. It was one of the largest boats sunk in World War II. “SS Champlain.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Champlain

Marilyn Shapiro, formerly of Clifton Park, is now a resident of Kissimmee, Fla. Keep Calm and Bake Challah: How I Survived the Pandemic, Politics, Pratfalls, and Other of Life’s Problems is the newest addition to her line-up of books. It joins Tikkun Olam, There Goes My Heart and Fradel’s Story, a compilation of stories by her mother that she edited. Shapiro’s blog is theregoesmyheart.me.