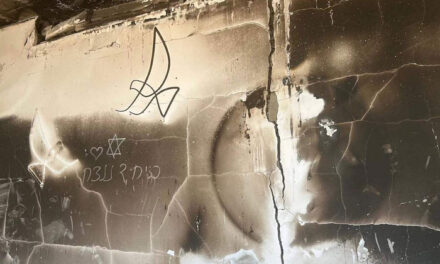

Praying for success in the war against Hamas, for the return of the hostages held by Hamas in Gaza and in memory of those murdered in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, at a prayer service at the Western Wall on Jan. 10, 2024. Photo courtesy of Chaim Goldberg/Flash90.

By TEVI TROY

JNS

Almost immediately after the horrific Hamas attack in southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, most Orthodox Jewish congregations began the practice of saying additional Tehillim (Psalms), usually chapters 121 and 130, after the three daily prayer services. In addition, many congregations, Orthodox, Conservative and Reform, added the short Acheinu prayer, a prayer for the release of captives that dates to the Middle Ages.

Praying For The Hostages

This 53-word prayer emphasizes the collective pain that the entire community feels over Jews suffering in captivity: “Our family, the whole house of Israel, who are in distress or in captivity, who stand either in the sea or on dry land, may the Omnipresent have mercy on them and take them out from narrowness to expanse, and from darkness to light and from oppression to redemption, now, swiftly, and soon!”

By my estimate, validated by a Wharton statistics professor, Jews around the world have said the Acheinu prayer more than a billion times since Oct. 7. I have personally said Acheinu more than 2,000 times since then, thinking every time about my deepest hope that they would somehow be taken “out from narrowness to expanse, and from darkness to light,” words that powerfully express what we now know to be the experience in the Hamas dungeons.

Many of the hostages prayed as well. Some were religious when they were taken hostage. Some became religious because of the experience. The sustaining of hope through prayer is often derided in Western liberal societies. The hostages themselves have attested to the agency that gave them, as well as power and hope. And a grasp on life itself.

They may also have benefited from knowing that they were being prayed for. Studies have shown that people who know they are prayed for fare better and return to health more often than those for whom prayers are not said. This is one of the reasons for the focus that synagogues have on prayers for health and healing, with the calling out of specific names of those who need healing.

Still, adding the prayers was unusual if not unprecedented. Orthodox Jewish prayers change very rarely, and not lightly. The first siddur, or prayerbook, dates to the ninth century; before that, prayers were generally recited by heart. The Jewish liturgy became more universal with the advent of the printing press in the 15th century and the creation of the first Soncino book. Although there are occasional changes based on new developments, such as prayers for the health of the relatively new State of Israel, for the most part, today’s Orthodox prayer service is little different than what the Soncino printers laid out in the late 1400s.

Helpful Activity

The tradition of saying prayers in times of need dates back to the Bible. In Genesis, Jacob prayed in advance of a dangerous meeting with his brother Esau, and Hannah prayed for a child in Samuel I. In Jewish law, Maimonides wrote in his Code, the Mishneh Torah, around 1180 C.E., that it is “permitted for a healthy person to read verses [from the Bible] or chapters from Psalms so that the merit of reading them will protect him and save him from difficulties and injury.”

Hashem On Our Side?

More than a century ago, German and British Jews had prayers for opposite sides in World War I. In World War II, however, Jews were more aligned against the German Nazi threat. In March of 1945, a joint declaration from Jews of three countries—Canada, the United States and the British Mandate of Palestine—called for “a day of fast and prayer … for the termination of this bloody war, and for the safe return of our sons and daughters.”

Of course, it’s not just Jews who pray in times of need. According to the Anglican Compass’ Jacob Davis, “Anglicans across the centuries have turned toward scripture, specifically the Psalms.” Many Christians also prayed for Israel specifically after Oct. 7, something we should be grateful for and consider a welcome boost.

A generation ago, Jews also responded to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 with prayer. In this period, Israel was facing the suicide bombings of the Second Intifada, which killed more than 1,000 Israelis, adding to the sense of need for additional prayers. There does not appear to be any one moment at which synagogues stopped saying extra Psalms in this period, but the immediate fear of a new attack in America eventually subsided, and Israel’s creation of a West Bank security fence helped quell the onslaught of Palestinian suicide attacks. One rabbi I spoke to told me that he stopped saying them in the fall of 2004, and that he feels that “special” prayers lose their specialness if they become permanent.

Halting These Prayers

Oct. 7 made special prayers necessary once again. Even as we prayed for the hostages, most people had little expectation that they would survive what Hamas had in store for them. While we mourn the 83 who did not make it, we must also celebrate the miracle that 168 have survived—an outcome no one would have imagined possible two years ago.

The release of the last living hostages has created a clean endpoint for the special prayers. Yet it is important to recognize the value of these billion prayers, even as they come to an end. Saying these prayers for the last two years gave seemingly powerless individuals agency during a difficult period and demonstrated a collective focus on the hostages’ return. At the same time, halting these additional prayers and returning to the traditional service now provides hope that we will not need these prayers again, as well as maximizing their potential effectiveness should they be needed again in the future.

Originally published in the Jewish Journal