Image courtesy of Deposit Photos.

By RICKI LEWIS

The recent diagnosis of stage 4 prostate cancer in octogenarian Joe Biden surprised many of us. How could an ex-president, presumably with top-notch healthcare, not have known at a far earlier stage? Symptoms were his first indication that something was amiss – and not the routine PSA blood test.

The reason for the seemingly delayed diagnosis? Age. With advancing years, some medical tests are no longer accurate predictors of disease.

Jewish people face higher risks of several types of cancer, including prostate. Our susceptibility, like other “Jewish genetic diseases,” stems from our small number of ancestors in Eastern Europe long ago. It isn’t just the BRCA genes that predispose us —in fact, a new prostate cancer gene more prevalent among Jewish people was discovered just recently.

Cancer Screening Tests

One perk of attaining a certain age is foregoing some health screens, as they become more risky, or annoying, than beneficial. Screens, like PSA tests or mammograms, indicate heightened risk, and the need for more specific diagnostic tests.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) releases guidelines for health care practitioners to consult upon evaluating a patient’s symptoms, medical history, and screening or diagnostic test findings. USPSTF is an independent, volunteer panel of national experts in disease prevention and evidence-based medicine — it isn’t government-affiliated.

USPSTF recommends:

- PAP smears until age 65

- PSA tests until 55 to 69, depending on family history

- mammograms until age 74.

- colonoscopies until age 75.

A caveat is clinical judgment — if a patient’s family health history indicates increased risk, then screening tests may be beneficial for longer.

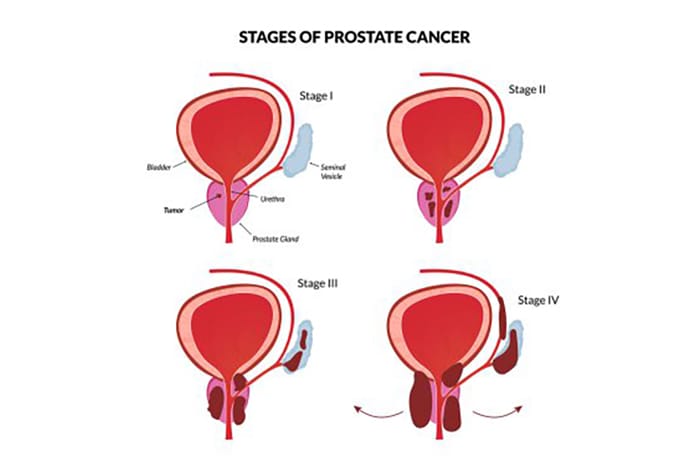

The Prostate

The prostate is a gland often described as resembling a walnut, wrapped around the urethra beneath the bladder. It produces a thin, milky secretion that activates sperm to swim.

Cells of the gland are festooned with protein molecules, called prostate specific antigen or PSA. The protein keeps other proteins, called semenogelins, from gumming up semen. If the gland enlarges, PSA level rises — and that can indicate cancer.

But PSA can also rise, transiently, from inflammation due to infection, or if a man has benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), which is common and isn’t cancer.

If infection and BPH are ruled out, MRI-guided biopsy for diagnosis of prostate cancer follows.

The Genetic Connection

Trigger warning: biology lesson.

In familial (inherited) cancers, a person is born with a specific mutation in every cell. That sets the stage for elevated cancer risk, so that, typically much later in life, a second mutation sparks the cancer. The type of cancer depends upon where that second mutation happens —if in a breast, then breast cancer; if colon, then colon cancer. In this way, an individual is conceived already halfway towards cancer. These are the cancers that run in families.

In contrast, the two mutations can each start in the same cell. If in a pancreas, it grows into pancreatic cancer; if in an ovary, then ovarian. Most cancers arise this way.

This concept is called the “two-hit hypothesis of cancer causation.” Although initially described in 1971, the idea has only recently influenced cancer treatment, with the recognition that certain mutations respond to certain drugs.

Today, mutations are routinely considered in personalizing cancer treatment, because some patients respond to specific drugs better than others. The jargony gibberish that flies by at the end of drug ads often denotes the targeted mutations.

Most of the dozens of cancer genes control DNA repair, which is normal and happens all the time. Derail a repair gene, and cancer mutations accrue and provide a cell division advantage. A cancer spreads.

Prostate Cancer Genes

A few genes bearing mutations that raise risk of prostate cancer among Jewish people are well known, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.

A mutation in BRCA1 raises risk of developing cancers of the prostate, breast, ovary, pancreas, Fallopian tube, bile duct, and others. The general population risk of prostate cancer is 12%, but for those with a mutation in BRCA1 it’s up to 26%.

BRCA2 mutations are linked to increased risk of prostate, breast, ovarian, pancreatic, uterine, and Fallopian tube cancers. Risk of prostate cancer is 19% to 61%, depending on family history and other conditions present.

Overall, people of Ashkenazi descent face a 1 in 40 chance of having a mutation in either BRCA gene —compared to the 1 in 400 chance among the general population. That’s a ten-fold increase.

Another well-known cause of elevated risk of prostate cancer among Jewish people is mutation in one of the genes that causes Lynch syndrome: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM.

Physician Henry T. Lynch was the first to describe the syndrome and attribute it to a specific gene, in 1966. Like the BRCA genes, Lynch syndrome in Jewish people stems from a long-ago founder mutation. Lynch syndrome is mostly linked to colorectal cancer, but mutations in the gens also lie behind cancers of the uterus, brain, stomach, small intestine, ovary, pancreas, ureter, kidney, bladder, gallbladder, and prostate. Several genes are now associated with Lynch syndrome.

A report on a newly-discovered prostate cancer gene was published just weeks ago – with first author none other than Henry T. Lynch, of the eponymous syndrome fame. The May 20 post from Johns Hopkins Medicine, “Study Suggests Genetic Mutation in Some Ashkenazi Jewish Men May Be Linked to Higher Prostate Cancer Risk”, summarizes a paper published in the April issue of European Urology Focus.

The newfound mutation is a “frameshift.” It’s a particularly devastating genetic glitch because it removes or adds only one or two DNA bases, like a typo that removes one or two letters from a sentence and then regroups the words into gibberish. The affected gene is called MMS22L. It’s an important discovery because the way that the code is garbled suggests that a type of drug, a PARP inhibitor, won’t work. And that can save time and spare a patient a pointless intervention.

Understanding cancer at the genetic level has opened up a world of new treatments, so that for many people, even with stage 4, life can go on — sometimes, for many years.

Ricki Lewis is a geneticist and science writer.