By DAVID ISAAC

(JNS)

The Jewish Community of Oporto recently announced it is working to preserve the 17th-century records of the Portuguese Inquisition. Under a protocol signed in 2019 between the Torre do Tombo National Archive in Lisbon and the Oporto Jewish Community, the latter undertook to pay for the preservation of 16th-century Inquisition case records.

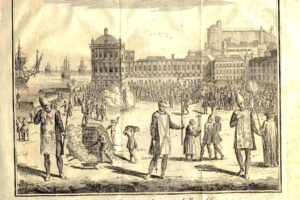

A Portuguese Inquisition auto-da-fé in Lisbon. Photo courtesy of The National Library of Israel.

Jewish History

The protocol, assisted by then-Israeli Ambassador to Portugal Raphael Gamzou, made it possible to recruit professional restoration personnel and set in motion the restoration and digitization of 1,778 court cases against “Jewish infidels” in three centers: Lisbon, Évora and Coimbra, the latter of which included cases from Oporto.

Now that work on the 16th-century archive is almost complete, the community would like to sign a protocol regarding the 17th century, according to David Garrett, a board member of the Oporto community. “So far we have only been able to preserve the legal processes, or cases, from the 16th century, of which there are about 2,000,” he reported. “These were, in fact, the most important because at that time the matrilineal genealogy of the persecuted was still known. That is, who were really Jews and who were not,” he told JNS.

He added, “We cannot forget that the Inquisition lasted three centuries, and even persecuted many non-Jews, Catholics of many generations who were still referred to as Jews with the sole aim of robbing them of their goods.”

The community first became aware of the decayed state of the records five years ago, when its representatives visited the archive. “In 2018, we were shocked when we visited Torre do Tombo together with Ambassador Gamzou,” Garrett said.

Millions Of Dollars Needed

“The Inquisition’s legal processes of the 16th century were practically lost. Many pages were already completely illegible and glued to other pages,” he said. “We decided to act immediately. Otherwise, the records would rot. It was possible to recover almost all of it, but not everything.

Meticulous Work

“To start the 17th century, we’re asking the Jewish world to collaborate on the project costs, because it cannot be that we alone should be the only ones involved in something so important,” Garrett said. The total cost of the operation to preserve and maintain the 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century records could reach as high as €3 million, ($3.4 million).

“It is scientific, meticulous work, page by page, word by word. It involves high-quality equipment, which is carried out by highly qualified professionals, whose salaries are naturally high,” Garrett explained.

The national archive is contributing 5% of the total cost, he said.

“For those who want to contribute, they should directly contact Torre do Tombo, the Jewish Community of Oporto or Ruth Calvão, head of project development and outreach at Centro de Estudos Judaicos de Trás-os-Montes,” he said.

Injustices, Atrocities

Calvão, president of the Center for Jewish Studies in Trás-os-Montes, said: “The deterioration of the archive items constitutes a real danger that the personal stories and testimonies about the historic injustices and atrocities [the victims] endured could disappear forever.”

The documentation at the Torre do Tombo National Archive concerning the Court of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and its courts in Lisbon, Coimbra, Évora, Tomar, Oporto and Lamego fill a hall 1,600 meters in length.

The Inquisition’s documentation has become the most reliable historical source about the Jewish community in Portugal.

The Catholic Church’s Tribunal do Santo Ofício (Inquisition) was established in Portugal to try crimes against the Christian faith and put an end to “heresies” and “apostasies.” If the victim of an Inquisition inquiry issued a denial, he would find himself in prison for months or years, enduring excruciating torture until a new hearing was scheduled. The prisoner was forced to pay all the expenses of the imprisonment, the trial and the torture. If convicted, all his property was confiscated.

Michael Rothwell, director of the Jewish Museum of Oporto, noted that, “the Portuguese Inquisition was in force between 1536 and 1831. Historian Cecil Roth said that since the beginning of history, there has probably been no time when such a systematic and long persecution was perpetrated because of such an innocent practice.”

Ashley Perry, president of Reconectar, an organization dedicated to helping the descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish communities reconnect with their Jewish ancestry, welcomed the preservation efforts. “The archives are in danger of being lost to time, which would be a tragedy, not just to our past but also the future as millions of people around the world are researching possible Jewish ancestry,” he said.

“The preservation and digitization of Inquisition records is essential to preserve our global Jewish history, because Portuguese Jews, many of whom had been forcibly baptized and forced to flee, formed the historic Jewish communities in the U.S., the U.K., the Netherlands and elsewhere. These archives are Jewish history, and we dare not let them disappear,” Perry said.

Confusion With Spain

Garrett noted that Portugal is behind Spain when it comes to preserving its Inquisition records. “Spain has invested a lot of money in its records,” he said, adding that unlike in Portugal, part of the Spanish archives are in the Vatican “because the appeals of the condemned were made before the Holy See and did not return to Spain.

“The Jewish world tends to confuse Spain with Hispania, i.e. the Iberian Peninsula, made up of Spain and Portugal,” Garrett said. “The difference of the total number of people persecuted in Spain and Portugal—300,000 and 40,000 respectively—has to do with the greater ferocity of the Spanish Inquisition and the fact that Spain is five times bigger than Portugal, discounting the colonies,” he said.

“These were, in fact, the most important because at that time the matrilineal genealogy of the persecuted was still known. That is, who were really Jews and who were not,” he told JNS.

“We cannot forget that the Inquisition lasted three centuries, and even persecuted many non-Jews, Catholics of many generations who were still referred to as Jews with the sole aim of robbing them of their goods,” he added.

The community first became aware of the decayed state of the records five years ago, when its representatives visited the archive. “In 2018, we were shocked when we visited Torre do Tombo together with Ambassador Gamzou,” Garrett said.

“The Inquisition’s legal processes of the 16th century were practically lost. Many pages were already completely illegible and glued to other pages,” he said. “We decided to act immediately. Otherwise, the records would rot. It was possible to recover almost all of it, but not everything.

“To start the 17th century, we’re asking the Jewish world to collaborate on the project costs, because it cannot be that we alone should be the only ones involved in something so important,” Garrett said.

The total cost of the operation to preserve and maintain the 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century records could reach as high as €3 million, ($3.4 million).

“It is scientific, meticulous work, page by page, word by word. It involves high-quality equipment, which is carried out by highly qualified professionals, whose salaries are naturally high,” Garrett explained.

The national archive is contributing 5% of the total cost, he said.

“For those who want to contribute, they should directly contact Torre do Tombo, the Jewish Community of Oporto or Mrs. Ruth Calvão, head of project development and outreach at Centro de Estudos Judaicos de Trás-os-Montes,” he said.

Injustices and atrocities

Calvão, president of the Center for Jewish Studies in Trás-os-Montes, said: “The deterioration of the archive items constitutes a real danger that the personal stories and testimonies about the historic injustices and atrocities [the victims] endured could disappear forever.”

The documentation at the Torre do Tombo National Archive concerning the Court of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and its courts in Lisbon, Coimbra, Évora, Tomar, Oporto and Lamego fill a hall 1,600 meters in length.

The Inquisition’s documentation has become the most reliable historical source about the Jewish community in Portugal. The Catholic Church’s Tribunal do Santo Ofício (Inquisition) was established in Portugal to try crimes against the Christian faith and put an end to “heresies” and “apostasies.”

If the victim of an Inquisition inquiry issued a denial, he would find himself in prison for months or years, enduring excruciating torture until a new hearing was scheduled. The prisoner was forced to pay all the expenses of the imprisonment, the trial and the torture. If convicted, all his property was confiscated.

Michael Rothwell, director of the Jewish Museum of Oporto, noted that “the Portuguese Inquisition was in force between 1536 and 1831. Historian Cecil Roth said that since the beginning of history, there has probably been no time when such a systematic and long persecution was perpetrated because of such an innocent practice.”

Ashley Perry, president of Reconectar, an organization dedicated to helping the descendants of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish communities reconnect with their Jewish ancestry, welcomed the preservation efforts.

“The archives are in danger of being lost to time, which would be a tragedy, not just to our past but also the future as millions of people around the world are researching possible Jewish ancestry,” he said.

“The preservation and digitization of Inquisition records is essential to preserve our global Jewish history, because Portuguese Jews, many of whom had been forcibly baptized and forced to flee, formed the historic Jewish communities in the U.S., the U.K., the Netherlands and elsewhere. These archives are Jewish history, and we dare not let them disappear,” Perry said.

Garrett noted that Portugal is behind Spain when it comes to preserving its Inquisition records.