By ALAN ZEITLIN

(JNS)

Ken Burns can’t recall ever learning about the Holocaust in school.

America’s most decorated documentarian, who boasts epic films like “Baseball,” “The Civil War,” “Jazz” and “The Roosevelts,” was asked by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum if he might make a documentary on the Holocaust. He decided to do so. Directed by Burns, Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein, “The U.S. and the Holocaust” is three episodes each about 2 hours.

The intent of the documentary is to show the way the U.S. responded to the Holocaust as it was happening and why.

For seven years, directors (from left) Sarah Botstein, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick went through thousands of documents and conducted numerous interviews to complete the documentary, “The U.S. and the Holocaust.” Courtesy of the documentary.

Burns remembers his father showing him a famed 1961 dramatic film about the trials of Nazis beginning in 1945 that included real footage.

“He made me watch ‘Judgment at Nuremberg,’ ” Burns told JNS. “The prosecutors pull down the shades and project the worst of the worst. He just asked me to look at it and understand what happened. … My father’s insistence was a searing memory. They did not hold back in the footage. There’s bulldozers, bodies and skeletons.”

Burns and Novick directed the 2007 documentary series “The War,” which had elements of the Holocaust. Burns said he was then approached by people with disinformation and conspiracy theories. That was partly a catalyst for making this film.

Answers to some big questions are juxtaposed with stories of Jews of the time, who were saved or slaughtered.

The moment where I cried the hardest was when actor Liam Neeson voiced Shmiel Jaeger, a man who moved to Delancey Street in Manhattan, found it to be unsatisfactory and returned to Poland. Years later, married with several children, his letter to his family in America asked for help to get him out of “this Gehenom” (Hell). In an earlier part of the film, he says in a letter to family members describing his plight, “when you go out into the street or drive on the road, you’re barely 10% sure that you’ll come back with a whole head or your legs in one piece.”

Heartbreak

Did Burns cry or have big emotional reactions while making the film?

“Every day,” he said. “It was seven years of a labor of love but also heartbreak. How could it not be? Sometimes, it was little, tiny moments. There was a journalist from Chicago named Edgar Mowrer. He understood what was going on in 1933. I don’t think he was anticipating the plan for the complete extermination of the Jews. But he was escorted out of the country by the Nazis, and while his minder was taking him to the train station, he asked him if he thought he’d ever come back to Germany, and he said, ‘with 2 million of my countrymen.’ I just burst into tears.”

The Roosevelt Question

Dorothy Thompson interviewed Adolf Hitler before he came to power for Cosmopolitan magazine and called him a little insecure man, but she read Mein Kampf. She let the world know that “not only are the reports about the atrocities unexaggerated, [but] they are underrated.” She wrote for The Jewish Daily Bulletin in New York, even though she was not Jewish, and this angered Hitler, who ordered her out of the country when she went back to Germany. We hear her say that “civilized people” didn’t believe Hitler would act in his anti-Semitism and warned that “Germany has gone to war already and the rest of the world does not believe it.”

Burns said this documentary is particularly meaningful. “I’ve said often that I won’t work on a more important project. I hope to work on other important films, but I will not work on a more important film than this one.”

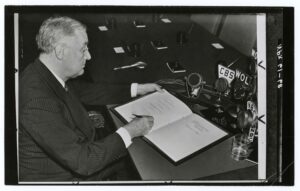

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Washington, D.C., Nov. 9, 1943. Photo courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration.

As to the argument of why President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not do more, we learn there was a real fear that if he pushed for more immigration of Jews, Congress might act to limit immigration or stop it altogether. The Hitler propaganda machine called him “Frank D. Rosenfeld” and the New Deal was called the “Jew Deal” with the anti-Semitic trope that the Jews were pulling his strings. We learn that Rabbi Stephen Wise met with Roosevelt and did his best to help Jews looking to come to America, as did several organizations, including the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

Lose-lose Situation

Burns said for dozens of years, people have asked him why American planes did not bomb the train tracks leading to the death camps. Some wonder why they didn’t bomb the camps as well. The film shows it was a complex issue. The Nazis could have likely rebuilt the tracks fairly quickly. In terms of morality, who is to say one would have the right to bomb the camps and kill Jews in that act, in order to save others? And what if American pilots were shot down trying to save Jews? What would have been the American reaction?

The documentary includes a mention from Holocaust survivor and Nobel Prize laureate Elie Wiesel saying it would have been worth it. Historian and current U.S. State Department anti-Semitism envoy Deborah Lipstadt appears several times. On this question, she says even if it would not have stopped the murder of Jews in the death camps, it would have been worth it to make a statement. But what would have been the optics of Americans killing Jews in death camps even if the intentions were good? Also, there weren’t precision bombs, and a one-off target bomb actually did land in a death camp.

“It’s a ‘lose-lose’ situation in a way,” Burns said of the difficult question. “People die.”

The Time Is Now

Burns said he had no idea when he started the documentary in 2015 that a few years later, the Tree of Life synagogue mass shooting in Pittsburgh would take place, followed six months later by the one in Poway, Calif., and then, in 2021, Jews would be beaten up in the street in broad daylight in New York and Los Angeles. He said due to his insistence, the film was released a year earlier than scheduled because it was needed to “enter the conversation.”

Lipstadt also notes that “the time to stop a genocide is before it happens.”

Nuanced Situations

Sarah Botstein, whose father Leon is the president of Bard College, said family members on her father’s side were wiped out during the Holocaust. She said she wanted to show the emotional aspects of the figures, the difficult questions and how many situations were nuanced.

Failures Of America

“The biggest challenge was trying to really thoughtfully interweave the events of the actual persecution of the Jews of Europe and the Holocaust with the question of what Americans, knew and when, and what they thought about it,” said Botstein. “Also, we wanted to show how America succeeded and how it failed.”

A measure of success came from bringing about 225,000 Jews to U.S. shores—more than any other sovereign nation, and defeating Hitler in war with Russia and England to end the Holocaust. A measure of significant failure came from not saving the lives of many when there was plenty of living space. Also stymying help for European Jews was the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 that stifled immigration, as it required visas, had difficult paperwork and would wind up being a barrier to saving lives. The refusal to accept the St. Louis, a ship with 937 passengers, most of whom were Jewish, was a disturbing development. The ship left from Hamburg, Germany and was set for Cuba until anti-Semitic sentiment caused the Cuban government to have a change of heart. This gave the Nazis the opportunity to say they were honest in not wanting Jews, while democracies claimed to want them but really didn’t.

Reports of murders of Jews were seen in newspapers; but they were not often on the front page. As for American villains, Breckinridge Long was an assistant secretary in the U.S. State Department who implemented policies to slow immigration, and in 1944 would be removed from his position overseeing the Visa Division after he either misrepresented facts or lied. On the radio, Father Charles Coughlin would spew anti-Semitism and scapegoat Jews. His program, heard by millions, was canceled in 1939. Madison Grant, voiced by Paul Giamatti, warned that taking in refugees would threaten America’s security and racial purity, saying that the Nordic race was superior. Sadly, no major movie studios took on the Nazis until Warner Bros. did so with “Confessions of a Nazi Spy” in 1939, starring Edward G. Robinson.

We learn that the Nazis, criticized for the treatment of Jews and the Nuremberg Laws, turned and pointed out the ill-treatment of blacks in America and laws that were unfair to them. It is claimed that Hitler may have believed that America would even tolerate the murder of Jews because of America’s treatment of Native Americans.

Historian Peter Hayes says in the film that while we like to think of America as welcoming, shutting people out is “as American as apple pie.”

Asked if he thought there could be another Holocaust, Filmmaker Burns would not comment but did say that he is concerned about what he sees. “I’m worried about the increase in anti-Semitism,” he acknowledged. “God forbid, we would ever approach anything like that.”