What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, presents iconic original illustrations and cartoons from MAD magazine’s longtime regular contributors, dubbed the “Usual Gang of Idiots,” plus next-generation visual satirists who found a home within the magazine’s zany zeitgeist.

>> CLICK: Introductory chapter to the book SEEING MAD

>> CLICK: A_Secular_Talmud_The_Jewish_Sensibility

“MAD was a groundbreaking magazine that influenced generations of readers and set the bar, and the tone, for contemporary humor and satire,” said Museum Chief Curator Stephanie Haboush Plunkett.

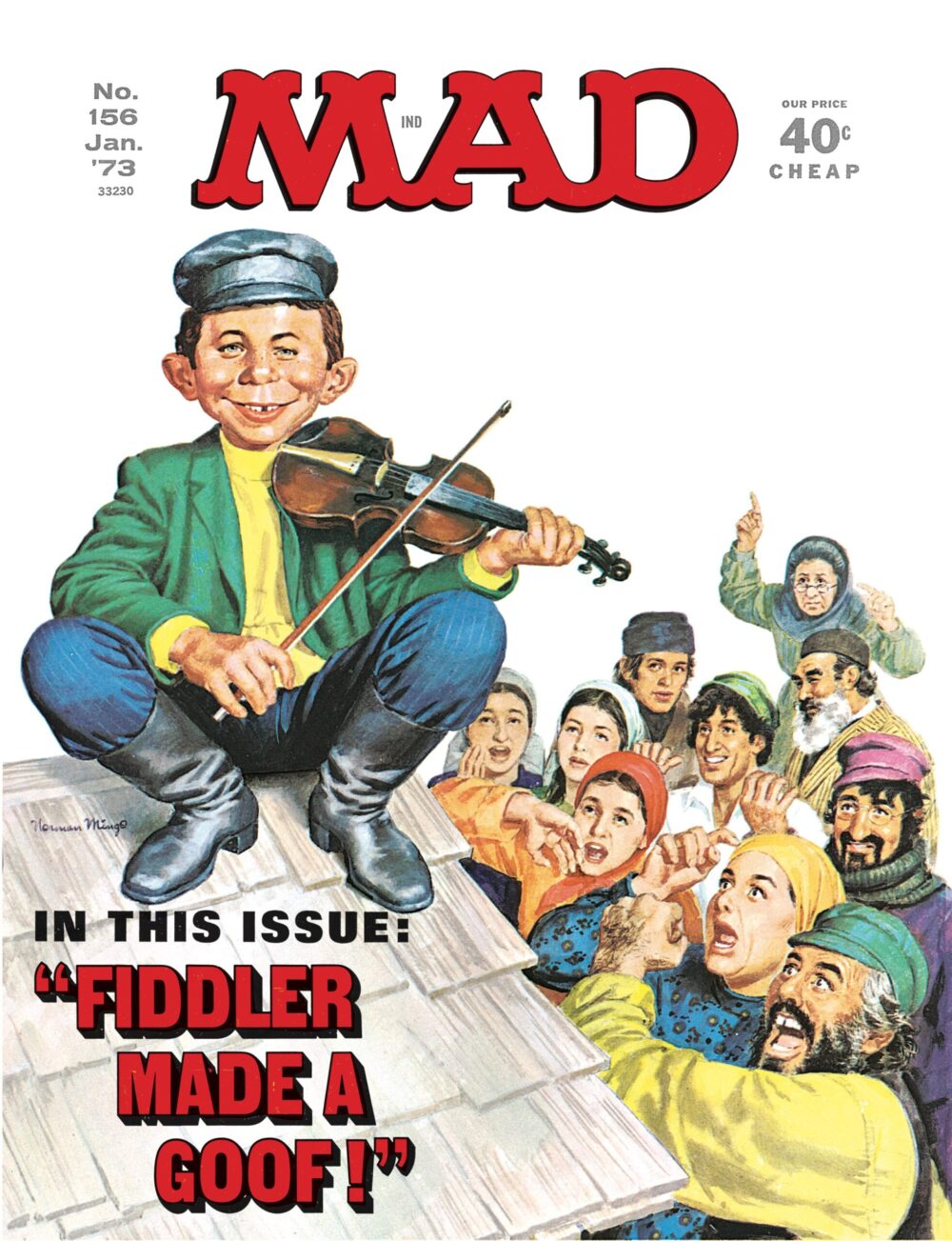

Titled for the defiantly nonchalant slogan of Alfred E. Neuman, MAD’s mascot and cover boy, “What, Me Worry?,” the show, running through Oct. 27, brings together original artwork, artifacts and memorabilia, photos, published ephemera, video content, interactive features.

Sections here are from “Introduction: MADness, Mishugas, Manhattan: Mad as the Other New York(er)” by Judith Yaross Lee, and Chapter 14: “A Secular Talmud: The Jewish Sensibility of Mad Magazine” by Nathan Abrams, in Seeing MAD: Essays on MAD Magazine’s Humor and Legacy, edited by Judith Yaross Lee and John Bird (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020). Reprinted by permission of the University of Missouri Press.

Silly and serious

Subversive, silly, serious, and shocking—often all at once—

MAD was controversial from the start in 1952. Ostensibly geared to kids, the publication discussed McCarthyism and the Cold War, political corruption, consumerism, celebrity culture, social and liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s.

MAD shaped the worldviews of Americans as did Norman Rockwell and other artists in decades of illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post and other mainstream publications. MAD’s subversive, shake-’em-up values and viewpoints diverged from Rockwell’s warm and gently humorous illustrations. In its sly and seditious art and spirit, MAD was a counter-cultural magazine that became a cultural powerhouse.

MAD was the first publication to ironically and humorously poke holes in all aspects of American life—from movies, television, music, art, and advertising, to superheroes, celebrity culture, and politics.

Laid groundwork

Laid groundwork

MAD’s irreverence, wit, cultural critique, and goofiness shaped the comic sensibilities and aspirations of generations of artists, writers, filmmakers, comedians, and other cultural figures. Comedy productions as diverse as Laugh In, Saturday Night Live, The Simpsons, South Park, The Onion, and The Daily Show all bear MAD’s influence, and celebrity fans including Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Jon Stewart, and Stephen Colbert have paid affectionate tribute to MAD.

Actor Michael J. Fox told Johnny Carson in 1985 that he knew he had “made it” in show business when MAD’s “Mort Drucker drew my head.”

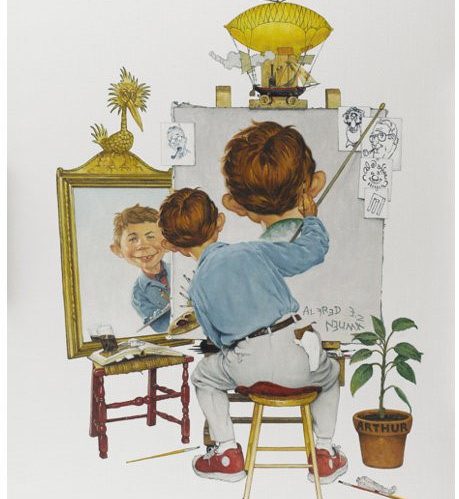

Among the gleeful targets of MAD’s wide-ranging parodies were Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post cover illustrations and advertising art. As a famous and revered illustrator, Rockwell, at the other end of the culture spectrum, was inspiration and foil to MAD’s contributors.

The exhibition features Richard Williams’ 2002 painting, Alfred E. Neuman’s Triple Self-Portrait After Norman Rockwell, created for the cover of the book Mad Art: A Visual Celebration of the Art of MAD Magazine and the Idiots Who Create It by Mark Evanier. The painting is a satirical redo of Rockwell’s humorous 1960 portrait of himself painting himself; in Williams’ rendering, Alfred E. Neuman sits in the artist’s chair, peers into the mirror, and paints, hilariously, the back of his own head.

Exhibition advisor William H. Foster III said, “MAD never surrendered to the darkness. It gave hope. It was an umbrella that shielded us to think freely…”

NORMAN ROCKWELL MUSEUM: 9 Glendale Rd, Stockbridge, MA 01262. Thursday – Tuesday: 10am-5pm. 413-298-4100

Sam Viviano, Alfred E. Neuman for President, 2008, Cover illustration for MAD #495, November 2008. Digital Design Director: Ryan Flanders. MAD and all related elements ™ & © E.C. Publications. Courtesy of DC. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission.

MADness, Mishugas, Manhattan:

MAD Jews as Outsiders –

Defending Democracy from Censorship Tyranny

Excerpts from: Introduction to Seeing MAD: Essays on MAD Magazine’s Humor and Legacy, edited by Judith Yaross Lee and John Bird (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020). Reprinted by permission of the University of Missouri Press.

By Judith Yaross Lee

mishugas, meshugas (Yiddish, n.), mih_shoo_gaas’ / meh_shoo_gaas’ / meh_shi_gaas’ / (varies regionally), craziness, madness, nonsense

prost (Yiddish, adj.), plain, lowly, humble; vulgar

In 1952, less than thirty years after the New Yorker reshaped American humor through sophisticated cartoons, humorous reporting, and comic fiction in a magazine famously “not edited for the Old Lady in Dubuque,” another local publication took an opposite approach—with possibly greater impact.

Scholars have not bestowed on Mad the loving attention given the New Yorker, nor named a school of humor after it, but both can lay claim to the title “America’s Most Important Humor Magazine.”

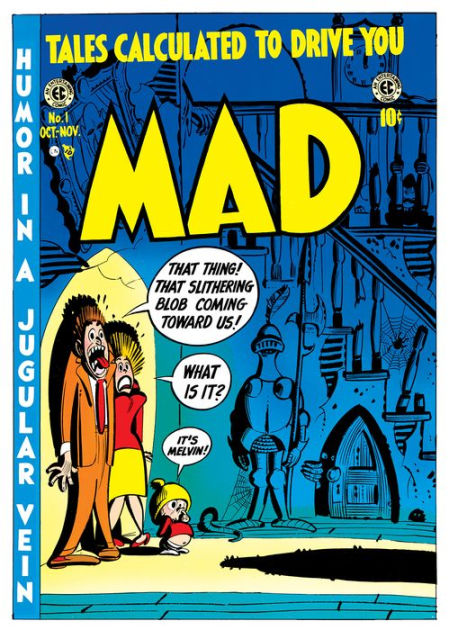

Mad founders Harvey Kurtzman and William Gaines did not write a manifesto akin to Harold Ross’s famous prospectus, but they didn’t need to. In place of Rea Irvin’s monocled dandy examining a butterfly on the New Yorker’s debut cover of February 21, 1925, an arch caricature of the nineteenth-century urbanity that Ross aspired to update, Mad’s first cover (dated October-November 1952, but on newsstands in August) reversed social norms to mock horror comics.

Focus on kids

As a crudely drawn mom and dad flattened themselves against

the wall of a dungeon, their hair literally raised in fear of “That slithering blob coming toward us!,” their toddler, belly button blazing, boldly produced the comic anticlimax: “It’s Melvin!” The clear message: Mad was a species of funnies aimed at comics fans more allied with the kid than the parents. This target audience reflected Gaines’s comics-business model of newsprint pages and newsstand sales at one dime per shot, not Ross’s more traditional reliance on glossy pages and advertising tied to the demographics of readers who could afford year-long subscriptions.

the wall of a dungeon, their hair literally raised in fear of “That slithering blob coming toward us!,” their toddler, belly button blazing, boldly produced the comic anticlimax: “It’s Melvin!” The clear message: Mad was a species of funnies aimed at comics fans more allied with the kid than the parents. This target audience reflected Gaines’s comics-business model of newsprint pages and newsstand sales at one dime per shot, not Ross’s more traditional reliance on glossy pages and advertising tied to the demographics of readers who could afford year-long subscriptions.

Where the New Yorker aimed at taste-making among the uptown yuppies of his day and “humor was allowed to infect everything,” as E. B. White put it, Mad took pride in a downtown adolescent tastelessness that defined mishugas— craziness, madness. (Foolishness gets dismissed as narishkeit, triviality.) Mad was, we might say, the Yiddish prost to the New Yorker’s Proust, but together the two magazines gave the U.S. its modern sense of humor...

Cultural outsiders

Mad’s brash exuberance diverged from the New Yorker’s more cerebral joking because the magazines’ editors and contributors reflected different worlds and worldviews…

[Unlike the sophisticated New Yorker writers]…Most of Mad s principals … were local boys from Brooklyn and the Bronx who had little or no college education… compared to Ross’s group, Mad staff and contributors were cultural outsiders several times over.

…the original Mad staff’s identity as outsiders—mainly Jews from the boroughs beyond Manhattan—more globally shaped its countercultural sense of humor.

… a Jewish identity is by definition counterhegemonic in a Christian society, which reinforces its worldview in Easter school breaks, the annual return of Scrooge, and Friday night lights that have nothing to with Sabbath candles; the western calendar makes Jewish holy days seem random when not invisible. Put otherwise, seeing the world through Jewish eyes, even nonobservant ones, means having skepticism toward majority belief, if not finding it incomprehensibly foolish. Feldstein delicately described the position as “a certain kind of living in society. Trying to survive in that society.”

…[Publisher Bill] Gaines testified voluntarily at the [1954 Senator Estis] Kefauver [Senate] hearings on juvenile delinquency, but he stood out, David Park has observed, as the sole comic book publisher to defend comics against the “middlebrow notions of taste” that they offended. Against Kefauver’s questioning, Gaines argued not only that censoring comics as unsuitable for children would set the U.S. on a slippery slope toward tyranny (“We don’t think that the crime news or any news should be banned because it is bad for children. Once you start to censor you must censor everything. You must censor comic books, radio, television, and newspapers. . . . Then you will have turned this country into Spain or Russia”)…

How Jewish is MAD?

… Notes from Jim Clevenson

With what seems like the “usual gang of idiots” running for president, it’s a relief to focus on Alfred E. Neuman, and take his advice: “What, me worry?”

Coincidence? I think not! — The Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, only an hour away in the lovely Berkshires, has devoted its main galleries to MAD magazine, which is partly responsible for subverting and rotting the brain of The Jewish World’s publisher, beginning in 1962, when, as an innocent child, he bought his first copy for 25 cents — CHEAP— on a foray to the local c-store for a loaf of bread — or was it a quart of milk?—both 26 cents in those days. Gasoline at the end of our street in Dover, NH, was 28 cents, and sometimes as low as 24 cents. In those days you sat in the car while the kid at the service station ran the gas —and checked your oil. The year my dad bought me a new black 26” one-speed Schwinn, a man’s haircut was $1, a boy’s 90 cents. I had been exposed to MAD by cousins Lenny and Jerry Groopman (now a famous Boston doctor and book author who writes for The New Yorker) on a visit to Great Neck shortly before. My literate newspaperman father forbade me and my sister comics, and frowned on MAD, but I caught him reading it, and laughing.

See above for links to the introduction and a chapter, “A Secular Talmud: The Jewish Sensibility of Mad Magazine,” by Nathan Abrams, from Seeing MAD: Essays on MAD Magazine’s Humor and Legacy, edited by Judith Yaross Lee and John Bird (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020). Reprinted by permission of the University of Missouri Press.

Abrams writes [excerpts]:

Mad magazine functioned as a secular Talmud for a generation of Jews and non-Jews alike in America and beyond. Like its religious forebear, Mad was inter-textual, self-referential, and arguably formatted in a similar way. And similar to the Talmud, its influence extended outwards—from the comic book world, it inspired graphic novels, television, the movies…

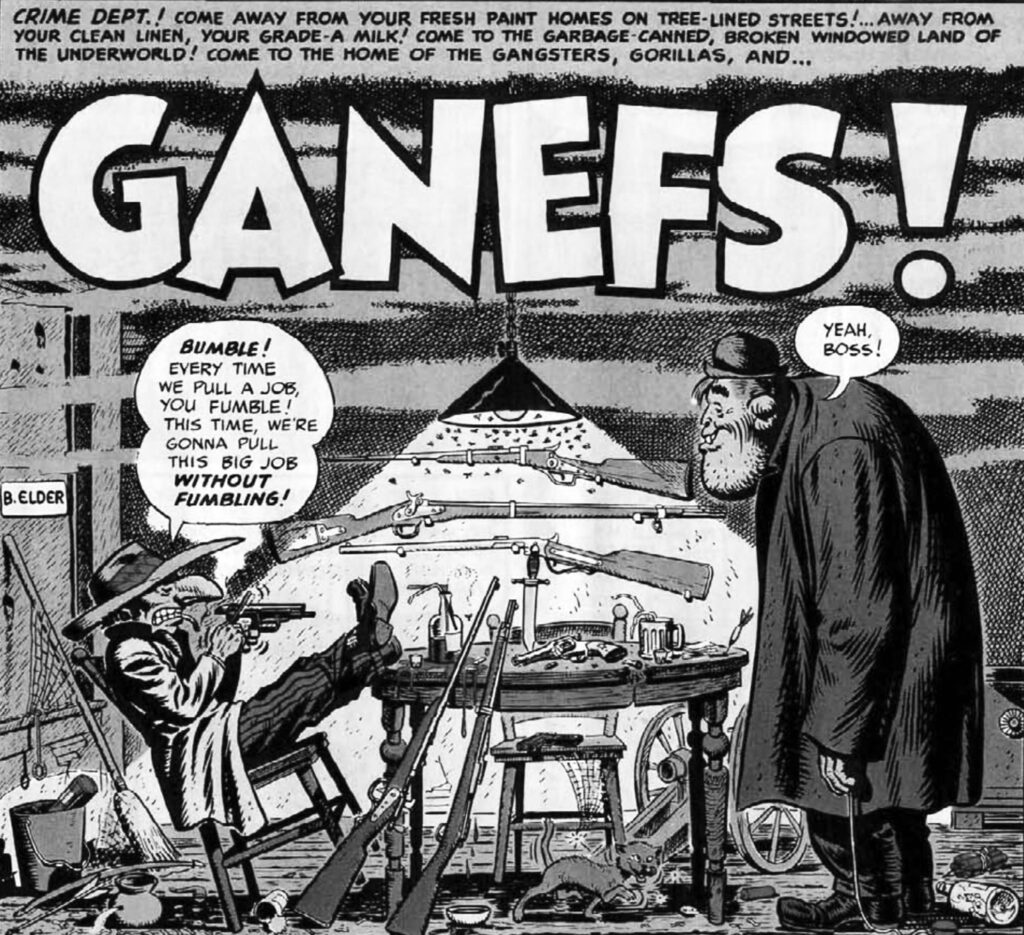

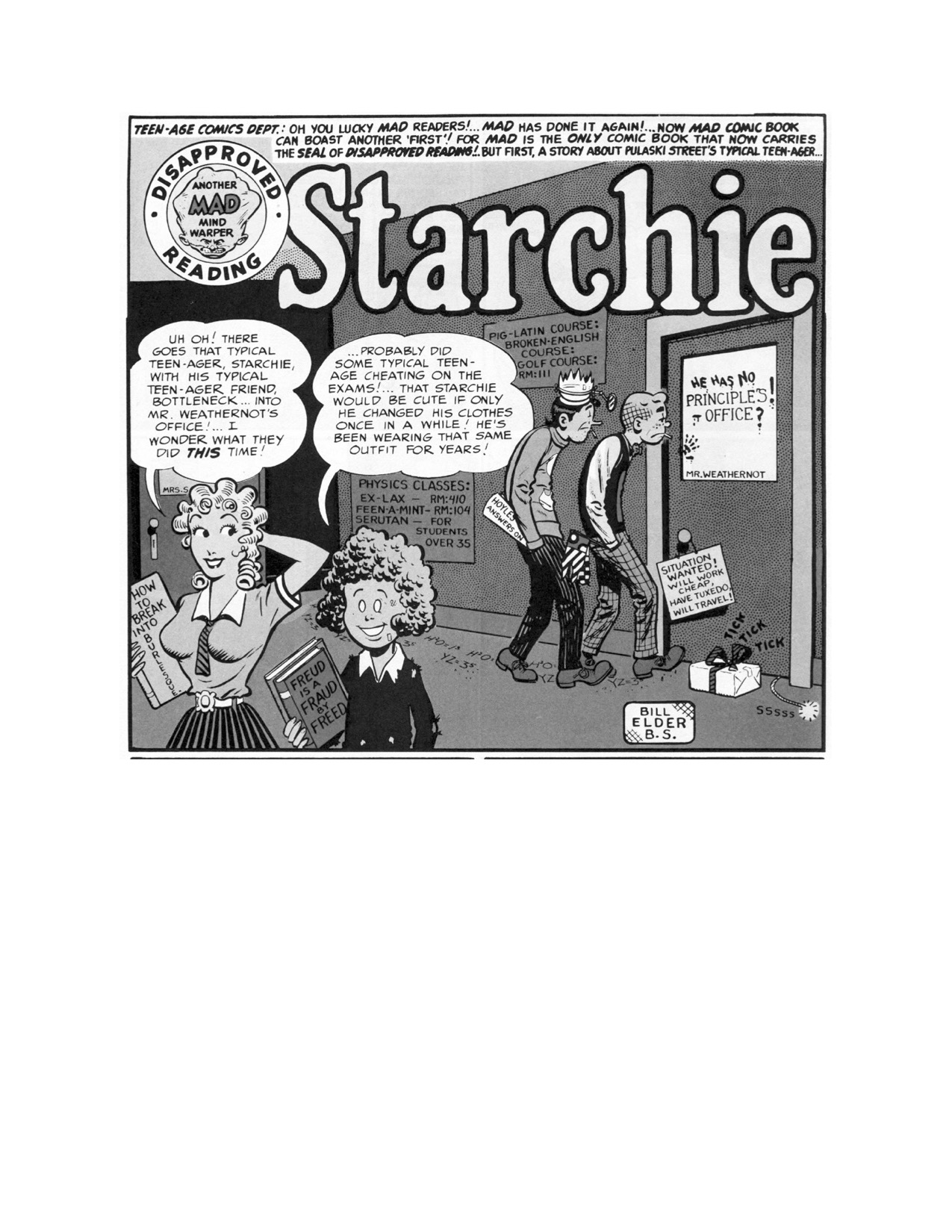

…Mad’s humor was grounded in Yiddishisms, sarcasm, and self-mockery, all defining features of Jewish humor. It employed a whole lexicon of Yiddish phrases, both real and imaginary, making Leo Rosten’s The Joys of Yiddish (1968) a required companion text for the uninitiated. …This flavor was announced from the very first issue when a strip entitled “Ganefs”—Yiddish for thieves or crooks—appeared. Mad’s Yiddish-inflected lingo also included the more familiar terms such as “schmuck,” as when it ran Al Jaffe’s strip “Don’t You Feel Like a Schmuck?!” (#157, 3/73). But this also included the less known, and often made up, words: schmaltz (chicken fat) shmear (spread on or for bread), oy (oh, no!), feh (ugh!), borscht (soup, ganef (thief), bveebleftzer (neologism suggesting “whatchamacallit”), farshimmelt (neologism for “all mixed up”), kibitzer (joker), schlepp (haul), schnook (fall guy), and halavah (ground sesame candy)…

Mad also took on Judaism…

The Jews do not believe Christ is their Savior.

Who do they believe He is?

They believe He is a nice Jewish boy

Who went into his Father’s business.

So much for our first lesson in religion.

Now you know why religion has been running for over 2000 years.

You also know why the Jews have been running for over 2000 years!