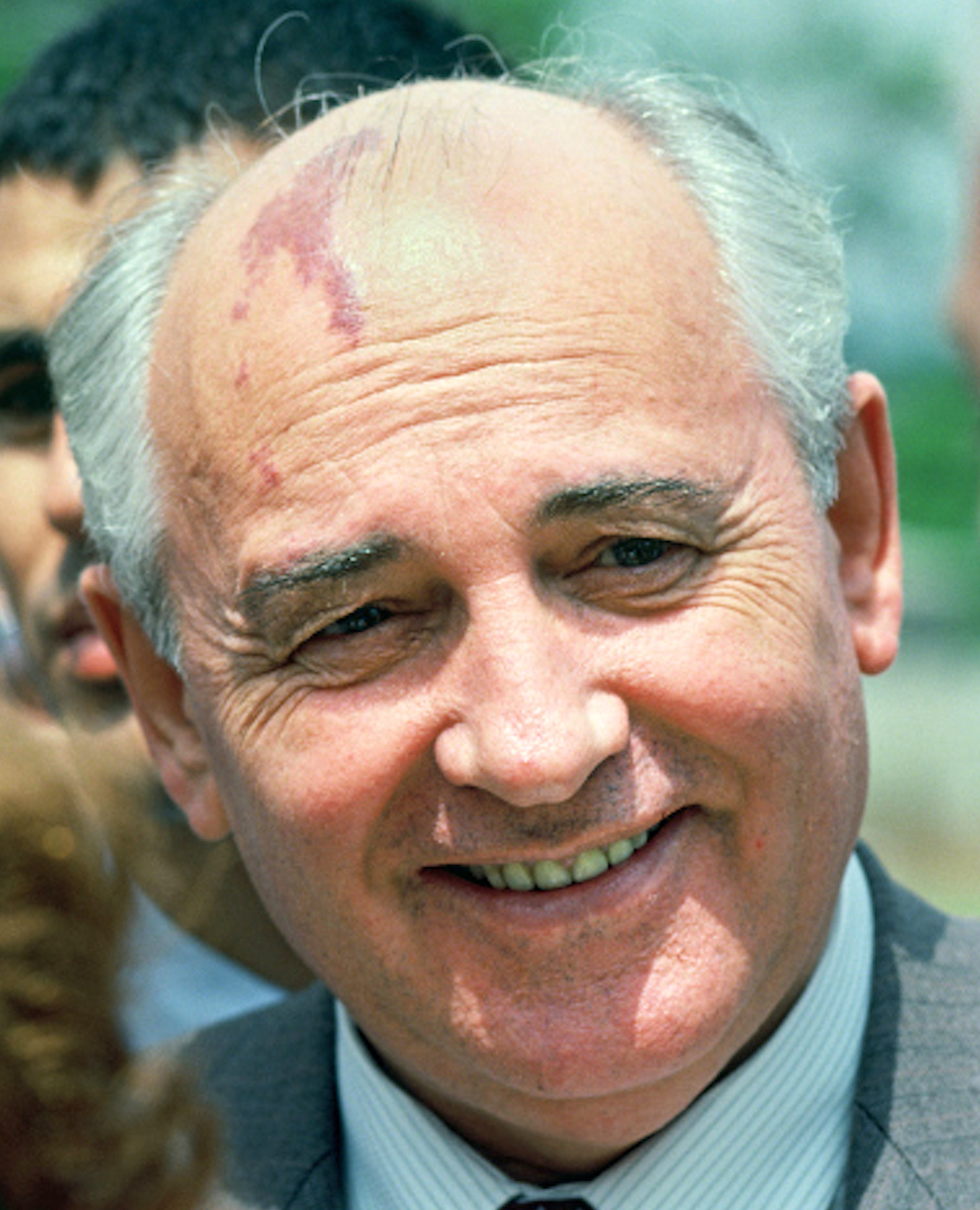

Freed Israeli hostage Eli Sharabi briefs reporters before a U.N. Security Council meeting in New York City on March 20, 2025. Photo courtesy of Loey Felipe/U.N. Photo.

By Rabbi AREYAH KALTMANN

JNS

We normally associate the name Eliyahu with the prophet who pays us a visit at the end of the seder, but this year another Eliyahu—the recently freed Israeli hostage Eliyahu (“Eli”) Sharabi—came to me early, sharing lessons of redemption and resilience.

As we gather around our Passover seder tables to recount our ancestors’ journey from slavery to freedom, we could find ourselves humbled by acknowledging a living embodiment of our ancestral narrative. Eli Sharabi, whose journey from the depths of captivity to the light of liberation, illuminates the very essence of our festival of freedom.

Questioning And Serving

In March, I had the chance to speak with Eli on the day after he testified at the United Nations. He bore testament to unfathomable darkness yet somehow he radiated light. Here stood a man who had every reason in the world to be mad at God and to turn away from emunah—from “faith.” Yet he continuously spoke of God, of unwavering belief, despite everything taken from him.

His gaunt physical appearance was reminiscent of a Holocaust survivor. I told him he reminded me of my own father—a Holocaust survivor who endured through seven camps, yet was always smiling, cheerful and exuded an unshakable emunah. Eli, like my father, believed in God even though it didn’t make sense.

Eli’s resilience reminds me of a story from the Holocaust, when a group of Jews in Auschwitz put God on trial. In their grief and anger, they found Him guilty; nevertheless, they adjourned their trial hurriedly to pray Mincha before sunset. This paradox reveals the essence of Jewish perseverance—questioning God while simultaneously serving Him with the utmost devotion.

While Eli was trapped 150 feet beneath the ground in the suffocating darkness of Gaza’s tunnels, he made sure to still say Kiddush every Friday night. As he raised his glass, his trembling hands held not wine but salty brackish water, he has reported. In that sacred moment, the salty drops transformed into something sweeter than the finest wine. From this dungeon of pain and agony, his lips recited ancient blessings. Each precious crumb of bread between his fingers became sanctified by an unbreakable faith in the face of desolation.

When he whispered his Friday-night prayers in his underground prison, it was not around a fancy table adorned with gleaming silver and fine linens. But his humble Shabbat prayers were holy. The contrast could not be greater: From the deepest depths of the earth to the highest realms of heaven, his prayers created a bridge between worlds. The melody carried the memory of his mother through the darkness, a defiant testament to faith unbroken.

As you read about the ancient ordeals of our ancestors’ enslavement, think about Eli Sharabi’s modern-day sacrifice. As you munch on your matzah around your table, think of how precious what it is you are doing. Regardless of how elaborate your seder is, know that God is happy that you are making the time to do it. In your homes warmed by family and tradition, you partake in a similar ritual to what sustained Eli in his darkest hours.

This is the essence of Passover. On Pesach, we are commanded to eat matzah—the humble bread of affliction—rather than leavened bread. It is in the matzah’s simplicity and imperfection that its holiness lies. So, too, with Eli’s makeshift kiddush. Had he possessed wine, he would have used it, but his makeshift salt water shows the intention and sincerity.

Freedom In The Mind

The word Mitzrayim (“Egypt”) also means “limitations.” Jewish tradition teaches that the celebration of “Yetziat Mitzrayim” is not merely about the historical exodus but about transcending our own internal constraints. Eli Sharabi’s unwavering faith, despite impossible circumstances, shows us the way. He demonstrated that true freedom begins in the mind and transcends our physical circumstances.

Faithful Persistence

A lesson of matzah, a flat bread, is that what is broken becomes more precious in spite of its brokenness. When we offer our best despite our limitations—when a hostage makes Kiddush with water instead of wine, when we pray despite our doubts—we create something more pleasing to God than perfection itself. It is not our flawlessness that God cherishes, but our faithful persistence despite our imperfection and lack of knowledge.

May this festival inspire us to recognize our own Egypt—whatever form it takes—and find the courage to cross our own personal seas toward redemption. May we carry forward the eternal flame of Jewish resilience just as Eli has done. We learn from him the lesson of what it means to be truly free, even when our bodies and minds are in shackles. This year, may we experience liberation from all internal prisons that hold us back from being our best selves and serving God with great joy.