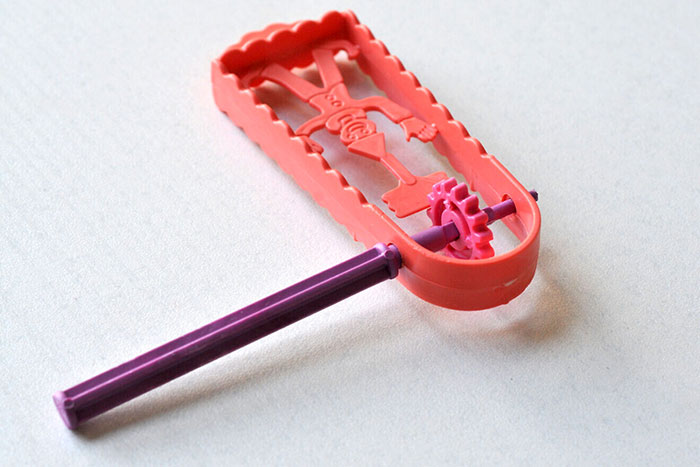

Illustration of a Purim grogger. Photo courtesy of Sophie Gordon/Flash90.

“Be this the whetstone of your sword. Let grief convert to anger. Blunt not the heart, enrage it.”— “Macbeth,” Act 4, Scene 3

The holiday of Purim is the most joyous of Jewish holidays and therefore our sages teach that when the month in which occurs, Adar, begins, joy increases. But given recent events, this year the joy of Adar may feel palpably less than in previous years. Many Israelis kidnapped on Oct. 7, 2023, are still hostages, continually brutalized and mocked, and the three that became the faces of that day’s treachery—Shiri Bibas, and her young sons, Ariel and Kfir—are now known to have been brutally murdered by Hamas and Hamas supporters back in November of 2023.

Zachor

We are all familiar with the tradition of making noise whenever the name of the villain Haman is mentioned during the reading of Megillat Esther (the “Scroll of Esther”). The reason is that Haman is understood to be a descendant of Israel’s arch-enemy, Amalek, who attacked the most vulnerable among us when we came out of Egypt. Scripture relates that in doing so, Amalek did not fear God; thus, their memory should be obliterated (Deuteronomy 25:17-19). It was Haman’s intention to finish what his ancestors began by exterminating every Jew in Persia.

Saul, The Liberal

The Shabbat preceding Purim is called Shabbat Zachor, the “Sabbath of Remembering.” The traditional Torah reading includes Deuteronomy 25:17-19, while the traditional haftorah recalls God’s command to King Saul to finally annihilate Amalek (I Samuel 15). Yet Saul chose to spare the life of the Amalek king, Agag. According to rabbinic tradition, not only did God take the throne away from Saul and his family, but Agag was able to reproduce. His son had children who had children—all the way down to Haman, who is called “the Agagite.” In other words, the one malignant cell left alive eventually metastasized into a greater threat.

In many congregations, I Samuel 15 has been replaced by another biblical text. The reason is that it calls for committing “genocide” on our enemies and because we Jews were ourselves victims of genocide, we should not be focusing on texts that countenance similar measures done to another group.

I would argue, however (and I know this will raise some eyebrows), that it’s not the same. There is no moral equivalency between what was done to us by the Nazis and what was necessary to be rid of Amalek/Haman. We Jews did not pose an existential threat to Amalek/Haman/Germany. Amalek/Haman did indeed pose an existential threat to us—and now Hamas and its supporters are following suit.

Authentic Jewish Approach?

Make no mistake—given Hamas’s rocket attacks on civilians, its atrocities on Oct. 7 and afterwards, the terror group and its supporters have clearly shown themselves to be Amalek incarnate. (It should also be noted that the Palestinian Authority’s policy of financially supporting the families of terrorists who are eliminated or incarcerated by Israel, infamously known as the “pay-for-slay” program, arguably puts them in the same category).

Yet there are still those among us who insist that desiring the total annihilation of our mortal enemies is somehow “un-Jewish” and that the “authentic Jewish approach” is to continue to pursue every avenue for a rapprochement, even with those who have sworn to annihilate us. To which one may fairly ask: How does one justify giving a state to people who are incentivized by their government to kill you? What is the logic behind such a response?

Several years ago, the left-leaning American intellectual Paul Berman wrote a book called Terror and Liberalism. He intended to demonstrate the difficulty many liberals have internalizing the existence of evil and totalitarian movements. He wrote that many of them believe that there is no such thing as pathological or irrational ideologies, “no movements that yearn to commit slaughters, no movements that yearned for death.” For them, the world was by and large a rational place with terrible atrocities indelibly linked to oppression—meaning, the greater the atrocity, the greater the oppression that must have caused it.

Irrational World

Certainly, such a mindset helps explain the tremendous support for Hamas and Palestinians, as well as the widespread condemnation of Israel from reliably “liberal” corners of society, especially from academia and the media.

Unfortunately, among those Jews who believed that the “world is by and large a rational place”—and that good intentions and helpful gestures toward our enemies will ultimately be reciprocated and bear positive fruit—was 83-year-old Oded Lifschitz. He was a lifelong peace activist who lived on the border with Gaza. He knew, worked with and trusted his Palestinian neighbors. On Oct. 7, he was taken hostage and then murdered by them. What happened to him prompted one wag to respond: “In that part of the world, political naiveté indeed can be dangerous to one’s health.”

Moreover, challenging the notion that not all Palestinians in the Gaza Strip support Hamas and its agenda are polls taken by Palestinians themselves indicating continuing overwhelming support for Hamas, as well as the testimony of freed hostages who, to a person, affirm that there is no separating Hamas from the rest of the Gazan population: Hamas is all Gazans, and all Gazans are Hamas.

With this taken into account, Israel continues to be accused of practicing genocide in Gaza, including by Jews who insist that Israel’s responses do not reflect authentic Jewish values. Some have accused it of doing so with the I Samuel narrative as an inspirational guide. To which one can rightly respond:

- Military experts have concluded that Israel’s military responses have not only been effective but arguably more moral than most any in the history of war; any civilian casualties in Gaza have been unintentional on Israel’s part and solely the intentional result of Hamas’s strategy to use civilians as shields and restrict their ability to flee.

Justification?

- Those who insist that authentic “Jewish” responses to terrorism and violence directed at us do not call for the annihilation of our enemies would do well to take a look at traditional Jewish texts—not only the conclusion of the Book of Esther itself but also Psalm 79, Psalm 83, the end of Psalm 137 and the teachings of the sages in Tractate Sanhedrin 72a ff (the source of the well-known adage: ‘When someone comes to kill you, be prepared to kill him first.”)

Given all of the above, am I justifying that we Jews practice bloodthirsty “genocide”?

No. I believe that the threat Jews face globally is existential and must be acknowledged as such. Just as there was no negotiating with the Nazis, there is no negotiating with Hamas and other terrorist groups like it. Moreover, unlike the Nazis who tried to hide what they had done, Hamas celebrates what they continue to do, happily broadcasting it to the world. Where we celebrate life, they celebrate death. Regrettably, the cultural differences are substantive and painfully irreconcilable. Thus, we should ask: How do we appropriately respond to ensure that our enemies have less physical proximity and the ability to harm us?

Of course, there are obvious reasons why we cannot respond as our ancestors did. Still, it is regrettable that in these so-called civilized times, we have been put into a position in which great numbers of our enemies may have to be eliminated just so that we can stay alive.

The operative word here is regrettable. Although the result of both Hamas’s actions and Israel’s actions is dead human beings, there is no “moral equivalency” because each begins with a different mindset. Like Amalek, Hamas intentionally attacks the most vulnerable among us—for years launching rockets into civilian areas, and, of course, butchering civilians in the most barbaric ways—all the while doing so with glee and public celebration.

Contrast this with Israel’s mindset: Doing everything it can to minimize collateral civilian casualties, intentionally using restraint that puts its own soldiers at risk, and expressing regret when civilians are among the victims.

Palpable Frustration

To be sure, Israelis may be responding with restraint and regret. But many may also be feeling some anger in their kishkes—not only anger at our enemies for what they’ve done to our bodies but also for what they’ve done to our souls.

This is why the above quote from Shakespeare rings true. And our frustration is palpable.

Indeed, the sounds of groggers may not seem so boisterous this year.

Rabbi Cary Kozberg is the rabbi of Temple Sholom in Springfield, Ohio, and the Jewish chaplain at Kensington Place in Columbus. He has been an advocate of Jews learning self-defense for more than three decades.