Saadia Dery, right, and Idan Siboni, center, with Alexandroni Brigade comrades. Credit: Courtesy of Idan Siboni.

jns

On June 20 of last year, Sgt. First Class (res.) Saadia Dery spoke with his wife, Racheli Orya Dery, by phone from the Netzarim Corridor in central Gaza, where he was stationed. The couple discussed plans for their second son’s first birthday and their wedding anniversary, both of which were just days away.

An hour after Racheli hung up, Saadia was killed in a mortar attack.

Milestones

Racheli, 29, marked both milestones during the shivah. A blue balloon shaped like the number one adorned the mourning tent at Saadia’s parents’ home in Eli, while the cemetery visit at the end of the mourning week coincided with the couple’s fifth anniversary.

A day after the shivah, Racheli discovered she was pregnant with the couple’s third child.

Solitude

For nearly six months, she kept the pregnancy to herself, attending all the prenatal appointments alone. Now, she prepares to face childbirth on her own too—a decision shaped by the profound solitude she has experienced since Saadia’s death.

“On one hand, he left me with an incredible final gift, but on the other, I can’t believe he left me to face this alone. It’s this overwhelming mix of life and death. With this pregnancy, I feel him inside of me so intensely, but I also feel his death in the most intense way possible.

“I can’t speak about this to anyone,” she told JNS.

Saadia Dery with his children, Hallel and Yinon Shaul Photo courtesy of Racheli Dery.

Alexandroni Brigade Has Added Focus

One of the first people she told about the pregnancy was Idan Siboni, Saadia’s commander in the IDF Alexandroni Brigade, a reserve infantry unit made up of veterans of the Golani Brigade. Siboni and other members of the platoon have made it their mission to support Racheli and her children, 3-year-old Hallel and 19-month-old Yinon Shaul, in every way, from organizing weekly grocery deliveries to taking her out on Saadia’s birthday in a bid to alleviate some of the pain.

Saadia was deployed to the northern border on Oct. 7, 2023, the day of the Hamas-led attack down south, and remained there for five months. Later, the platoon was deployed to Gaza, where he was killed. The platoon’s third deployment was in Southern Lebanon, fighting Hezbollah terrorists.

In a plea made shortly before his death, Saadia asked the others in his unit to take care of his wife and children in the event that something should happen to him. “We fought on three fronts, but fighting for Racheli and her children became our fourth—and possibly our most important—mission yet,” Siboni said.

Money Concerns

Saadia’s platoon has organized a crowdfunding campaign to buy an apartment for Racheli. As the widow of a fallen soldier, she receives monthly stipends from the Defense Ministry, including a rental stipend (paid directly to the landlord) capped at 3,000 shekels (about $810). That stipend is only available to those renting apartments costing up to 6,300 shekels, and exceeding that amount disqualifies her from receiving any rental assistance.

During the recent wave of air-raid sirens warning of Houthi missiles from Yemen—one of which hit less than half a kilometer from her home—the heavily pregnant Racheli had to wake her baby and toddler and carry them down flights of stairs to the bomb shelter.

Remaining in Jaffa holds deep significance because of how much the city meant to Saadia. But it’s nearly impossible to find a sufficiently sized apartment in the area that includes a safe room within the 6,300 shekel rental cap.

“He believed living in Jaffa and strengthening the community was part of his life’s mission,” Racheli said. “He was an emissary in everything he did in life.”

The five years of their marriage were the happiest of her life, Racheli said. “I would ask myself all the time, is it really possible for it to be this good?”

Her life until then had been far from easy, shaped by her parents’ turbulent divorce during her teenage years and the devastating loss of her father two years before she met Saadia at age 22.

Anxiety

Sitting on the couch in her small but tidy apartment, Racheli noted the significance of the day—it was her father’s yahrzeit, a detail that added weight to her reflections. Saadia didn’t just step into her life—he stepped into her family’s as well, often taking on her absent father’s role by offering guidance to her five siblings.

When Saadia informed her that he was being deployed to Gaza, Racheli’s heart plummeted. Until that point, when he had been stationed on the northern border, she had been crippled with anxiety, exacerbated by caring for a toddler and a four-month-old through incessant rocket sirens.

“But when he said that awful word—Gaza—that was it for me. The feelings of anxiety were replaced with a feeling of total certainty. I knew then that he wouldn’t return from this war,” she told JNS.

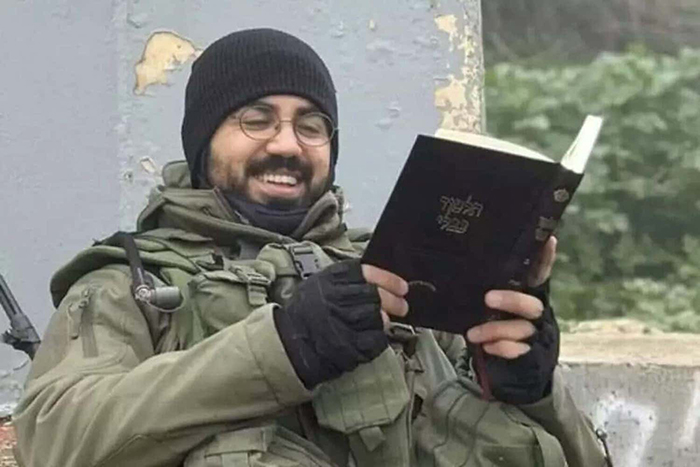

Saadia Dery studying Talmud in Gaza. Photo courtesy of Laly Derai/Facebook.

Did He Know?

Despite his optimism—about winning the war, about the progress of the IDF—and his constant reassurances that he would be fine, Saadia’s actions told a different story. During a break from the front, he put everything on hold: his university studies, his rabbinical training at a Jaffa yeshivah, and he went out of his way to find a replacement in his work as an aide for autistic children. (Full disclosure: Dery was an aide for this reporter’s child]. “It felt like he knew he was going to die and was tying up loose ends,” Racheli said.

Memories

During the furlough, Saadia insisted that he wanted to do something every day with Racheli alone or with the children. Each day, he planned something—picnics, restaurant outings, a trip to the Ramat Gan Safari.

“Every outing felt like he was experiencing it for the last time,” Racheli recalled, noting how she couldn’t stop taking photos. The feeling was so strong, she said, she even snapped pictures of mundane moments like washing his children’s hair. “I just knew it was the last time he would bathe them.”

When the time came to return to Gaza, Racheli begged him not to leave. He had received sick leave due to a cold, but he insisted on going back two days earlier than planned. “Nothing I could say would stop him,” she said. “He believed so fully that this was his duty, to fight in a war for our existence. He would say to me, ‘Imagine me asking you to stop the most important thing in your life.’”

For many months, she conjured images of his funeral and shivah in her head, knowing that any moment a knock on the door from military representatives would be the death knell confirming her worst nightmare.

When the knock came, one day after his return to Gaza, she saw the officers through the peephole. At that moment, a silent prayer flickered through her mind. “Let him be wounded—even critically—that I’ll somehow deal with.”

When they delivered the news that would change her life forever, she collapsed to the ground, her children in the room with her. “When people speak about this moment, they always say it feels like the ground beneath you just gives way. That’s what it felt like exactly. I just screamed and screamed at the top of my lungs.”

Now, sitting on the couch in her apartment, Racheli broke down again as the memories overwhelmed her. A phone call informing her that Saadia’s brother Avraham was on the news to speak about the fund-raising campaign, jolted her back to the present.

Listening to Avraham appeal to the anchor about Racheli’s plight, an oversized image of Saadia in uniform looming on the screen behind him, was surreal. “I just can’t grasp that he’s talking about me. It doesn’t feel real.”

Avraham and fellow reservists from the Alexandroni Brigade extolled Saadia as a hero of Israel. There was talk of how he proved that it was possible—despite haredi objections—to be both a Torah scholar and a dedicated IDF soldier.

Racheli bristled at some of the praise. “It’s all true of course. But I want people to know not just the war hero, but the man he was on a personal level. This man—my man—who was an exceptional father, the perfect family man. That’s enough, without turning him into a symbol of grand, lofty ideas and ideals. I want people to know that he was goodness itself, and that he was the love of my life.”