By DEBORAH FINEBLUM

(JNS)

Arguably the most important Jewish holiday that a good many Jews know little about, Shavuot celebrates nothing less than our Jewish forebears receiving the Torah some 3,300 years ago (hence the Hebrew moniker—Zeman Matan Torateinu, “the time of the giving of our Torah”). Perhaps even more fateful, it marks the moment when they agreed to abide by it. Sight unseen.

“We will do and we will hear,” they swore, defying that logic thinking that would have expected the reverse order.

And on Shavuot (beginning this year on the evening of Thursday, May 25, and running through Saturday at sundown on May 27 in the United States), the Jewish people are meant to feel like they are receiving the Torah and making that Divine deal with the creator all over again.

Here’s the test:

- Shavuot started out as a harvest holiday. What is a recent Israeli addition to its lore?

- Why don’t most Jews make a big deal of Shavuot, as they do on Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Passover and even Chanukah, which religiously is somewhat small potatoes?

- How many days after Passover does Shavuot fall, and what’s the goal of that time period?

- Why does Shavuot last only one day in Israel and two days in the diaspora?

- Why is Shavuot an all-nighter?

- What’s the relationship between Shavuot and teen confirmations?

- Why is Shavuot a special holiday for Jewish converts?

- Why is Shavuot an equal-opportunity holiday?

- What’s with the cheesecake?

- Why do you see so many recently clean-shaven men on Shavuot?

Some answers to reflect upon:

- Long before Shavuot became a celebration of receiving the Torah, it was known as the Feast of Weeks and designated a harvest holiday. At this time of year in Israel, the first of the fruits are ready to be picked, and the custom grew up to deliver a basket of the best of one’s first fruits to the Temple in Jerusalem—a sign that our ancestors knew exactly whom to thank for the success of their crops. “That’s one reason that Shavuot has always been a time to express gratitude,” says Rabbi Binny Freedman, rosh yeshivah of Orayta in Jerusalem. A case in point is this piece of 20th-century Jewish history: It was on Shavuot in June 1967—just six days after the Israelis took back the Old City in the Six-Day War—that the Western Wall (Kotel) was officially opened to the Israeli public. For the first time in nearly 2,000 years, Jews could pray at the Wall, and some 200,000 of them poured in that day, all celebrating their newfound freedom to worship by those ancient stones.

- The holiday lacks the trappings that make its fellow celebrations so appealing, explains Rabbi Chaim Wolosow of the Chabad Center in Sharon, Mass. “On Passover, you have the matzah and all the other symbols; on Sukkot, you have the lulav and etrog, and the sukkah But on Shavuot? Even the cheesecake and ice-cream are relatively recent traditions.”

- Shavuot falls 50 days after Passover, a time when a ragtag bunch of escaped slaves miraculously coalesces into a unified people worthy of the gift of Torah. During these days, as Jews count the days of the Omer (signifying the gifts of the humble grain of barley in ancient times), they also work on self-improvement, so going forward they’re worthy of the Torah and other assorted blessings. “The Torah, which was given in the wilderness, reminds us that there is no place so inhospitable that Torah can’t find its place there,” says Rabbi Melanie Aron, rabbi emerita at Congregation Shir Hadash in Los Gatos, Calif. “And no period of our life so barren that the Torah cannot enrich it.”

- Like other festivals, Shavuot was celebrated for two days outside of Israel because, at a distance, it was hard to know exactly when the holiday rolled around. Although for nearly 2,000 years, Jews the world over have been able to rely on the calendar, the tradition of two-day festivals in the diaspora remains unbroken. In addition, there is a spiritual rationale for the difference, says Wolosow. “Kabbalah teaches us that in Israel, you are already so close to God, you can absorb the power of the holiday in just a day, whereas for us in the diaspora, it takes a full two days to absorb it.”

- Tradition has it that—though advised they needed to stay up the night before they were scheduled to receive the Torah from Mount Sinai—the Jewish forefathers fell into a deep slumber. To make up for their lapse, many Jews throughout the centuries have stayed up all night and learned the books of Jewish wisdom. The custom goes back, it’s told, to 1533, when Rabbi Joseph Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch, a guidebook to Jewish law, invited his colleagues to learn with him on Shavuot. Besides Torah, Talmud and Mishnah, many also learn the Tikkun Leil Shavuot (“Rectification for Shavuot Night”) with its excerpts from the 24 books of Tanach. Legend has it that Caro and others living in the Ottoman Empire at the time were able to stay awake, thanks to the region’s potent Turkish coffee. In recent years, many have also fortified themselves with coffee (increasingly strong brews as the night wears on) and the now-traditional cheesecake and ice-cream. “The Tikkun Leil Shavuot? It’s something that goes beyond rational understanding,” says Rabbi Avraham Sutton, a popular Torah teacher around Israel and online and author of Spiritual Technology: On the Transition From Profane Technology to Sacred Technology in Preparation for the Great Shabbat, among other books. “Though we’ve been given Torah to learn every day, it’s our learning on Shavuot that not only makes us worthy of receiving the Torah anew but also makes an opening for all our learning the rest of the year,” adds Sutton, who’s stayed up learning and teaching every Shavuot since 1972.

- The tradition of confirming teens began in German 200 years ago in the early years of the Reform movement, says Rabbi Aron. “The first idea was that at bar/bat mitzvah age, kids are too young to truly understand Judaism and commit fully, but by the late teen years they are much more mature.” Reason two? “To give girls an equal opportunity for learning Jewishly,” she adds.

- On Shavuot, Jews the world over read the Book of Ruth, the earliest record of Jewish conversion. But what’s the connection between this poignant story of loyalty, faith and devotion, and the receiving of the Torah? Rabbi John Carrier, a Jew by choice who’s the spiritual leader of the Pasadena Jewish Temple and Center in Pasadena, Calif., has a theory. “The Book of Ruth is a story of free will; Ruth freely chooses that ‘Your people will be my people and your God my God.’ Now we have the opportunity to freely choose—we accepted the responsibility at Sinai; Shavuot is a time to accept it all over again, in each of our lives.” Something that resonates with the rabbi’s own experience: “There were people who held the door open for me many years ago and now I want to pay it forward and hold the door open for others learning about Judaism.”

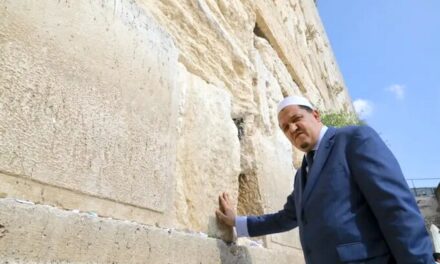

- Moses was told by God to invite everyone to the revelation at Sinai, and God spoke these words: “Today, you stand before Me—all of you, your leaders and your followers, your children and your wives, even the stranger; all of you, from the woodchopper to the water-drawer, stand before Me to enter into this covenant. And I make this covenant not with you alone, but both with those of you who are standing before me today and with those who are not with us here today” (Deuteronomy 29). That spirit of inclusion continues to be a hallmark of Judaism, says Jay Ruderman, whose Ruderman Family Foundation supports initiatives for including those with disabilities in Israel and around the world. “We all stood together at Sinai, regardless of background or ability,” he says. “The moment when we were the closest we ever were to God was a time of complete inclusion when we all heard God’s voice—a voice and a message of inclusion that we can still hear in our Torah.”

- The tradition of eating dairy on Shavuot comes down through a number of different influences, according to Beth A. Lee, author of The Essential Jewish Baking Cookbook: Traditional Recipes for Every Occasion. One of her favorites is the image of Israel as “the land of milk and honey”; God promises to take the children of Israel to a “good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:8). “And the most wonderful modern version of milk and honey,” says Lee (who has a Jewish food blog, OMG! Yummy), “is the sweet and creamy dessert we know as cheesecake.”

- Many Jewish men leave the razor untouched from Passover until Lag B’Omer (the 33rd day of the Omer, when it is said the 24,000 students of Rabbi Akiva stopped dying so the Jewish people can stop mourning) and others stay bearded until just before Shavuot. One of those who eschew the razor from Passover to Lag B’Omer is Victor Lejtman of Baltimore. It’s a tradition that’s become more accepted in the workplace over the years, he reports. “It used to be that it was expected you would show up at work in a suit and clean-shaven,” says Lejtman, who’s in the computer field. “But now that business casual is the norm, beards are far more accepted.” Except for some random itchiness and the fact that neither his wife nor his mother likes the beard, he happily continues to grow his Omer-spring facial hair. “It’s all part of the tradition of semi-mourning that we have for the students,” he notes.

Missed a few? You are not alone. Just remember to keep the coffee hot, the cheesecake available and your books (and mind) open for an unforgettable holiday.