Moss Haggadah—In Every Generation ©2024 David Moss. Graphic courtesy of Bet Alpha Editions.

By HILLEL KUTTLER

JNS

One of Passover’s central themes is that participants at the seder, the interactive experience at Jewish families’ dinner tables that opens the annual holiday, should internalize the Israelites’ exodus by seeing themselves, even millennia later, as personally having been liberated from slavery in Egypt.

Artist David Moss took the Hebrew word lir’ot, to see, to heart.

In Every Generation

In a Haggadah he began working on in 1980, Moss presented that theme across two facing pages. As the pages begin to be opened, the portraits of six Jews on each of three rows—garbed in the clothing of various historical periods—reflect off shiny surfaces on the facing pages, as if all 18 people are looking into mirrors. When the pages are fully opened, the seder participant notices himself or herself in the faux mirrors.

“The reader now is facing all the mirrors and actually sees him or herself reflected dozens of times between and among the historical Jews, literally exemplifying the texts: We must see ourselves as if we came out of Egypt in every generation,” Moss said in an interview with the National Library of Israel.

Moss designed the one-of-a-kind Haggadah on commission from Richard and Beatrice Levy of Florida—and now the work is in the NLI’s collection, a gift in August 2024 from Trudy Elbaum Gottesman and Robert Gottesman, who purchased it at a Sotheby’s auction.

The Haggadah is “a deeply researched, modern, visual interpretation of the traditional text” and is a commentary on both “the traditional text and … on our collective historical memory and its meaning,” said Dr. Chaim Neria, curator of the NLI’s Haim and Hanna Solomon Judaica Collection. A Sotheby listing remarked that each page “makes a visual and intellectual statement that surprises, delights and educates the viewer.”

A Story Of Aliyah

A native of Dayton, Ohio, Moss was living in San Francisco when he decided to begin working on the project. He had wanted to move to Israel and his late wife, Rosalyn, suggested doing so in stages. The Haggadah project proved to be a key spur in their journey to settling in the Jewish state.

Before sharpening a pencil or mixing paint, Moss conducted six months of research on Haggadot, including at the NLI and at the British Library, in London. He studied the history of the Haggadah text’s development, traditional commentaries on the book, and the art history of Haggadah manuscripts.

Moss first worked on the artistic side of the project in Jerusalem.

Moss Haggadah—Or leHametz ©2024 David Moss. Graphic courtesy of Bet Alpha Editions.

“I began the Haggadah in Jerusalem, knowing well that it would be sent into the diaspora, but even over 40 years ago I had a strong desire that somehow, sometime, my manuscript would return to Jerusalem,” Moss, who has lived in Israel’s capital since 1983, said in a video conversation from his studio in the Hutzot HaYotzer artists quarter outside the Old City’s walls.

“So of course it was an unimaginable thrill to actually witness the return of the Haggadah back to Jerusalem literally as I predicted 40 years ago …, to my city, to Jerusalem.”

At the time of the commission, Moss was enjoying a career as an artist specializing in designing ketubot and penning the traditional Jewish wedding contract’s calligraphy in Aramaic. He landed the Haggadah commission just as he sought a longer-term project.

“Fresh Insights”

The Levys extended artistic latitude, requiring only that the Haggadah be in large format (its dimensions are 18 x 11½ inches: 458 x 292 mm), be on animal parchment and be in traditional style—the last parameter representing a shift for Moss, whose work tended to be “quite modern and graphic,” he said.

“I basically wanted to allow the text itself to reveal new insights, unique ways of approaching the text, fresh insights that had never been done before,” he said.

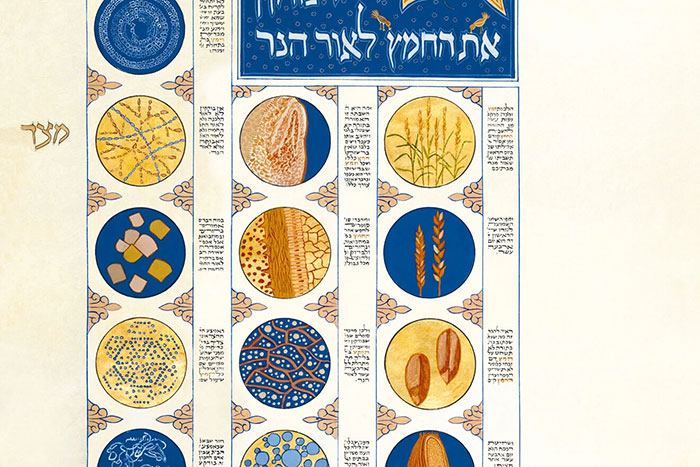

Moss used gold leaf and various artistic techniques throughout the work—not, he explained, to experiment or to extend his range, but as “the perfect way to express” his understanding of the relevant text in the Haggadah.

With a few exceptions, such as the aforementioned mirrors, Moss’s approach was: “Idea determines technique,” he said.

“I used papercuts when they expressed the concepts I wanted to convey,” Moss said, citing his employing the technique on both sides of one page to convey the multiple concepts conveyed by the Hebrew root avd to mean slavery, work, idolatry and worshipping God.

Replicas Available

“The silhouettes are identical, but the first side of the page shows the slavery in Egypt. When turned, the same cut-out silhouettes show the baking of the matzah: divine service,” he said.

Replicas of the Haggadah have been produced, and Moss teaches from it in presentations to groups and individuals throughout the year. But Moss said he never uses his own Haggadah at seders he hosts, which typically extend past 3 a.m.

Uses Others’ Haggadah

He celebrated this Passover at Camp Ramah in California, in Ojai, Ventura Country, where he is a scholar in residence. At Moss’s seder were his sister, his daughter, her husband and their three children. He usually uses a newly published Haggadah, offering fresh insights into the experience.

The Moss Haggadah is on display at the National Library in Jerusalem during Passover, as part of library tours.

This article originally appeared in The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.