By MENACHEM WECKER

(JNS)

Isaac Akiba in the Boston Ballet’s 2013-2014 season. Photo courtesy of David Akiba/Courtesy of Isaac Akiba.

Isaac Akiba, 34, knows what it’s like to end a professional dance career—twice.

In 2019, the decision was made for him after a ghastly injury, tearing his anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, live on stage in “The Nutcracker” at the Boston Opera House. His doctor told him he’d never dance that part, with its complicated, saut de basque jump again, but less than two years later, he was back on stage performing it again.

Then, on June 4, he retired from dancing on his own terms, amid tears, laughter and friends. “Everything seemed very familiar because I had done it 1,000 times. But it was the last time I was doing everything, and I was very aware of that,” he said.

That decision was a year-and-a-half in the making, including seeing a sports psychologist, Akiba told JNS. “I felt it was absolutely the perfect time,” he said. “It was incredibly emotional. I’m still processing.”

When he starts an M.B.A. program at Boston University this September, it will be his first time entering a classroom as a full-time student since high school. In the interim, Akiba, who identifies as Modern Orthodox, is studying at Ohr Somayach in Jerusalem, which he planned to do in summer 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted everything.

Akiba also aims—through the American-Israeli Ballet Association that he founded—to put the Jewish state on the international ballet map.

“My goal is to create a center,” he told JNS. “I want the Israel Ballet to be known as one of the best ballet companies in the world, for it to tour internationally and for people to connect with Israel through the art form of ballet. That’s my hope and dream.”

Female Stereotypes

Growing up in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, Akiba attended public schools. One day in elementary school at Agassiz Elementary School (since shuttered) when Akiba was 9, two Boston Ballet representatives came into his classroom.

They lined up the class, told the kids to go up on their toes and tested each one’s flexibility. Akiba was given a white, sealed envelope at the end of the day.

“I ran home,” he told JNS. “I was very excited about it.”

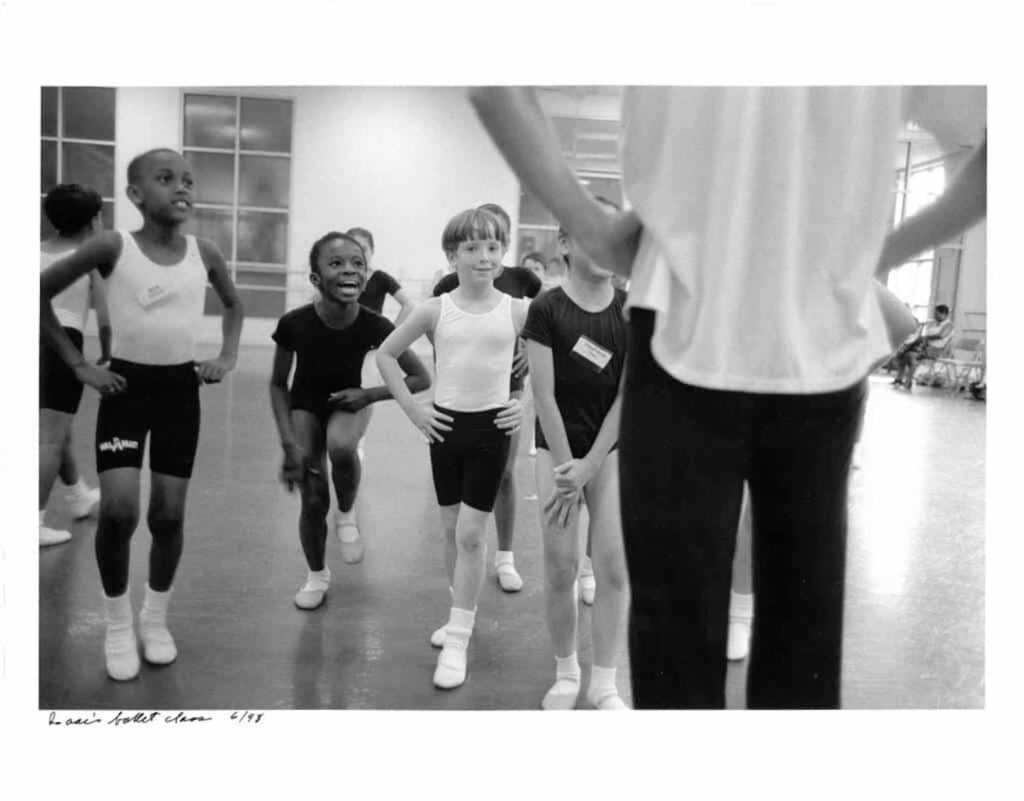

A 9-year-old Isaac Akiba studying at the Boston Ballet in June 1998. Photo by David Akiba/Courtesy of Isaac Akiba.

Whole New World

He insists that the letter was still sealed when his mother opened it. Inside was an invitation to a 10-week outreach program called City Dance, which brought 9-year-olds to the Boston Ballet’s South End headquarters for weekly instruction.

“It was a great introduction,” he told JNS. “Ballet has these female stereotypes:—that you’re a pansy or something. Or you’re weak if you do ballet.”

None of his five siblings—he is second to last—danced, nor did his parents. They were both professional photographers who taught at Emerson and Babson colleges, and encouraged him to join City Dance.

Akiba had no prior interest in dance but was very athletic. “I knew I wanted to impress them,” he recalled of the two ballet representatives who came to his elementary school. Soon he was donning tights and a leotard, as well as leather slip-on shoes, in a large studio with ballet barres along the walls.

“It was this whole new world,” he told JNS.

The program—made up of half boys and girls, and which was culturally and racially diverse—involved running, jumping, fun exercises and improvisation to music. It was not yet competitive.

By age 15, Akiba realized he could do ballet competitively. “I was good at it. I was talented. I was coordinated, had the physique,” he said. “But at the same time, I was a typical, lazy teenager.” He had gone on to Washington Irving Middle School and then attended high school at Boston Arts Academy. After he completed the 10-week program, Akiba stayed on as a Boston Ballet student. There, he met two boys with whom he became very close. One, who was also in his high school, came from Miami and the other hailed from Italy.

“I realized that these kids were leaving their families, leaving their lives to come study at Boston Ballet, while I was ungrateful for this world-class education,” he told JNS.

As their friendships grew, Akiba figured their passion for dance rubbed off on him, or as he put it, “ignited my fire for it.” He became very focused. So focused, in fact, that he dropped out of school.

‘Just Wanted To Dance’

During Akiba’s junior year in high school, he was able to make an ambitious schedule work. He took ballet and then academic classes in the mornings at Boston Arts Academy, and then he went to Boston Ballet classes in the afternoon. The high school ballet was not nearly as advanced as the afternoon training, he said.

That came to a head—or toe—when his high school schedule shifted midway through his junior year, and he had to choose between it and Boston Ballet. “We had multiple meetings, and they just turned us down,” he said of the high school administrators.

His parents and his teachers weren’t thrilled, but he dropped out of high school. “I hated school. I just wanted to dance. I just wanted to be in the studio. That’s all I wanted to do,” he told JNS. (Several years later, when he was 23, he got his GED.)

Isaac Akiba and another dancer backstage at the Boston Ballet running to their next entrance during the ballet’s 2013-2014 season. Photo by David Akiba/Courtesy of Isaac Akiba.

Then 16, Akiba was spending full days at Boston Ballet.

“Your life becomes dance. You take it everywhere ‘to go’ with you. It’s not like you leave the studio and you become something else,” he told JNS. “You leave the studio and you go home. You try to eat the right things, so you can feel good tomorrow. You do your exercises. You try to get enough sleep so you can have the most amount of energy. You look at videos. It constantly surrounds you.”

Dancers get used to sticking their feet and legs in buckets of ice. They wrap their legs in compression materials. They do yoga, cross-training. And that doesn’t include rehearsals, private teachers, tutors and coaches.

“It’s not just a physical thing,” he said. “It’s an emotional thing.”

Being in the limelight in public performances came naturally to Akiba. “I loved doing it,” he said. “I would just come alive.” He also used the word “elevated” and said he achieved “this next level of performance.”

It was only when he started college—an online degree in leadership with a business minor at Northeastern University—that Akiba realized he was also good at studying and academic work. In high school, he figured, he could have done well if he’d only cared.

At Boston Ballet, Akiba participated in a 2006 competition in Beijing and earned a silver medal at the World Ballet Competition in Orlando the following year, when he was part of Boston Ballet II, a program for up-and-coming dancers. He was promoted in 2009, became second soloist in 2012 and soloist in 2013, according to a Boston Ballet profile.

The Accident

When a dancer tears an anterior cruciate ligament live on stage in a show like the “Nutcracker,” it turns out, per the cliché, that the show must go on. Another dancer stands in.

Akiba had seen a couple of others tear their ACLs doing that particular Russian dance, with a lot of torque on the knees. He took off for a turning jump, and when he landed, his knee snapped. In a lot of pain, he hobbled off into the theater wing and collapsed.

Life Changes

Colleagues carried him downstairs into the physical therapy area, and a doctor checked on him. The next day, he got an MRI, which revealed a full tear of his ACL. The physical therapist told him, “You’re never doing that dance again.” Akiba remembers thinking, “‘No. I’m going to do it again.’ It was crazy. That was my goal.”

“One moment I’m throwing myself flying through the air. The next moment, I can barely walk,” he said.

His mother and sister were in the audience that day: Dec. 22, 2019. Akiba’s father had died just months earlier after a 10-month battle with cancer. His father had been a big supporter of his dancing and would bring him to his classes and wait outside the studio until he finished.

Two days before his dad died, Akiba’s niece was born. Akiba had the chance to see his dad—then in very bad shape at home in hospice—become conscious momentarily when he held his newborn granddaughter.

“You can kind of see death and life all at the same time,” he recalled.

It took a dream—in which he sensed his dad, after the latter’s passing, telling him that he was doing well—for Akiba to feel released from the pain of his dad’s death. He was able to start dancing again. He went on tour to Canada. Then on a Sunday night, his mom and sister were in the audience to see him in “Nutcracker” for the first time without his dad.

Akiba felt excited and high energy, and he wanted to uplift his mom and sister. The two made their way backstage and were escorted to the physical therapy room to join him.

He had surgery in January 2020, mere weeks before the pandemic seemed to start. And as he had predicted, he returned to the stage in November 2021, intentionally performing the same dance that had sidelined him as his first one upon returning to the stage.

“It was incredibly intense,” he said.

Isaac Akiba and another dancer backstage at the Boston Ballet running to their next entrance during the ballet’s 2013-2014 season. Photo by David Akiba/Courtesy of Isaac Akiba.

But at this point, Akiba had a Jewish community behind him, and some 30 people had shown up to the theater to support him. “It was such a success. I feel like I’ve never danced better,” he said. “I was super nervous, but it was a process to do that jump again. I took a year-and-a-half to do that jump again.”

‘Guided’ And ‘Blessed’

Akiba grew up in a Reform Jewish home, which was culturally Jewish. His father was an atheist, but would join the rest of the family in synagogue for High Holiday services at Temple Israel in Brookline, Mass.

The family had Shabbat dinners every Friday night. Akiba’s mother was adamant that her children have Jewish identities.

As his 13th birthday approached, Akiba felt totally absorbed in ballet. But his brother, who became Orthodox (and is now a Breslov Chasid) said that he should do the bare minimum and at least be called up to the Torah for an aliyah on his bar mitzvah.

Akiba had enough Hebrew Sunday school under his belt to know the blessings, and he had his bar mitzvah at Aish HaTorah—then at Coolidge Corner in Brookline.

At the time, dance and Judaism felt separate to him. But he now sees connections between the two. Akiba, who talks about “God awareness” in himself, told JNS that both ballet dancing and religious practice involve discipline.

“Just as a ballet dancer gets up and has morning class every single day, a religious person gets up and says the morning blessings,” he said. “It’s a routine. It’s a lifestyle.”

As he was preparing to come back from his injury, Akiba became more interested in and involved in Judaism. “I just felt really guided, and I felt like I was so blessed,” he said. “And I felt like I was helped from above to be able to accomplish this goal of mine.”

A Cultural Boost

He may need further help as he seeks to better introduce Israeli ballet to the world, with hopes of helping it do the kind of cultural diplomacy for the Jewish state that the Bolshoi Ballet does for Moscow and the Royal Ballet does for London.

“These are things that the British and the Russian people are so proud of. They travel all over the world. People are familiar with these countries and with the arts in these countries because of their formidable dance companies,” he said.

He is aware of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the Batsheva Dance Company and the Israel Museum. He thinks his connections and experiences, coupled with his passion, can help Israel make an even larger cultural name for itself.

“It’ll help Israel and the Jewish people in their success,” he affirmed. “I think it will help assuage anti-Semitism as people connect to Israel in a new way.”