By MIKE WAGENHEIM

(JNS)

Discussions between the United States and Russia over the potential release of Americans Brittney Griner and Paul Whelan from Russian prisons have been making international headlines for months now and are starting to rev up. In the thick of those talks is an Israeli, Mickey Bergman, the vice president and executive director of the Richardson Center for Global Engagement. He works beside the former New Mexico governor and U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Bill Richardson to help free Americans being held prisoner or hostage aboard, serving as a conduit on behalf of the captives’ families.

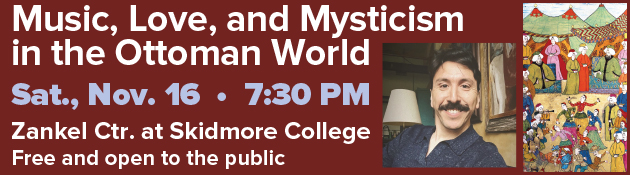

Mickey Bergman, vice president and executive director of the Richardson Center for Global Engagement.

Bergman, a native of Tel Aviv and former paratrooper in the Israel Defense Forces, was recently involved in successful efforts to free former U.S. Marine Trevor Reed from Russia and Jewish American journalist Danny Fenster from Myanmar.

JNS spoke with him about the status, process and intricacies of the Griner/Whelan talks, as well as the efforts to free Fenster.

The interview has been edited.

Q: Obviously, these are very delicate negotiations that are going on right now with Russia and trying to free the Americans being held prisoner there. Can you give us a little synopsis of where things stand in the process right now?

A: I think that specifically with Brittney Griner—the fact that her trial is over, her conviction and her sentencing—allows for the next stage to take place. I know there’s an appeal, but right now, negotiations can actually happen in earnest between the two governments. Hopefully, that will lead to her and Paul Whelan’s return. But as you can imagine, these negotiations are complicated. I think we’ve seen a little bit of the public spat over this the last few weeks with [U.S.] Secretary [of State Antony] Blinken’s public comment about it, and then Foreign Minister Lavrov responding publicly. I think it takes time for the governments to settle in and to even negotiate who needs to negotiate with whom and when before they actually get into the substance.

Q: If it’s trying to figure out where each government stands, then where does the Richardson Center and Bill Richardson fall into place? Are you serving mainly as a go-between? Are you representing the families’ interests?

A: Let me take a step back. The Richardson Center for Global Engagement is the center that Governor Richardson established and that I work with. We are a non-government, not-for-profit organization. We work on behalf of families at their request and at no cost to them. The fact that we’re non-government means that even though we don’t represent the U.S. government—we represent the families—we do coordinate with the U.S. government at times, especially when it makes sense. Those relationships are intense as you can imagine they are, but we don’t carry the authority of the government and don’t pretend to. We are very, very clear. In some cases, we’re able to solve the problem ourselves. For example, nine months ago, we went to Myanmar, Burma, where Danny Fenster, a journalist from Detroit, was held there for six months. We were able to have a conversation—to develop a relationship and convince the leader of the Burmese military government to release him to us with nothing in return. We were able to do it by ourselves without the U.S. government. In the case of Russia, because there’s something asked in return, an exchange of prisoners can only be authorized by the U.S. government. Our role is a little bit different. We try to catalyze, we try to accelerate things, because when governments talk to governments, even if they want to talk only about prisoners, the rest of the bilateral issues come into play. With Russia, we have a war in Ukraine, we have conflicts around. We have nuclear issues. There’s just a slew of things that complicate any negotiations. When Richardson comes into this, we’re not the government, so we cannot talk policy. We solely focus on prisoners and humanitarian issues, which allows us to have informal conversations, listen much better to what the other side is saying, and be able to decipher from it what a deal might look like that can be seen by both sides as a win. And then we actually have the work of negotiating or convincing our own government in doing that deal.

Q: Your organization has tie-ins and connections there to Moscow. Bill Richardson served at the United Nations with now-Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. The Trevor Reed negotiations weren’t that long ago now. What have you learned about the folks you’re dealing with in Moscow—how they operate, what they’re essentially looking for?

A: That’s a complicated question, and we cannot get into all the details around it, but it’s true in February, the end of February, actually, the eve of the war, Governor Richardson and myself were in Moscow at the invitation of the Russians. We met with the Russian leadership to discuss Paul Whelan and Trevor Reed. That was before Brittney Griner. At least, it wasn’t known that she was detained. And we came back with clear ideas of what the Russians were willing to do and the deal that they wanted to do, and we went back and we presented it to the White House. None of it was groundbreaking. It’s things that we’ve discussed with the Russians and the White House has discussed with the Russians before, but what was interesting at that moment is that the Russians were still saying that a deal is on the table. Even despite the war that was raging at that point in Ukraine and we were trying to push [to free] Trevor Reed, who had active tuberculosis. So, we said there’s urgency. We worked very closely with the Reed family and Jonathan Franks, who represented them, and made sure that they met with U.S. President Joe Biden. And then we applied our own pressure in our conversation with the president basically to push towards making that urgent deal in spite of the war or the conflict between the countries. Now, that gives me hope that it’s doable to do it again from that perspective. But there are a lot of moving parts. Everybody’s talking about the two major cases: Whelan and Griner. There are other Americans being held in Russia. It’s a bigger issue.

And there is not only the issue of the prisoners; [Russian] President [Vladimir] Putin is looking at the impact that this has on his own agenda. U.S. President Joe Biden is looking at it from a political perspective as well. It’s very complicated, and the key is to just find the overlap between the two sides at the right moment and push for it to see that it happens.

Q: How do you make the case where we’re going to trade you one of the world’s most notorious arms dealers for somebody who got caught with a few grams of marijuana? How do you kind of negotiate that when they’re not equal in any measure?

A: On this, I have to say it’s a difficult thing, but it’s really important for your audience to understand these deals, these exchanges, they’re not just. You’re looking at a convicted criminal versus people who are wrongfully detained. Even if Brittney Griner confessed, you actually have to think about it as a hostage confession almost. So, this is not about justice. This is a political deal, and the important thing to understand is that there are almost 70 Americans being held around the world now, wrongfully detained as defined by the U.S. government. They’re held mainly because they are Americans. We have an obligation to do what needs to be done to bring them home. Nobody likes it. It’s not just. But it is the right thing to do for these Americans, for their families and for our nation. And as for the people who claim that it might make more Americans vulnerable, making those deals: I would argue two things. First of all, the data doesn’t support that. The deterrence factor doesn’t come from the deal you make. It comes from your behavior after the deal is made. Actually, if you look at one of the leading countries in this, it’s Israel. And in the way they will make the deals, they will do what needs to be done to bring back Israelis. But then anybody that has been involved in the kidnapping knows that there’s a target on their head for the rest of their lives, and that’s where deterrence comes from.

Q: The kind of behavior that we’re seeing at this point in time—usually, I assume, you’re trying to keep these things under the radar. You try to keep these talks quiet and not drum up a whole lot of publicity. In recent weeks, the U.S. government has been making a lot of noise about this suddenly. Did that help to jolt efforts forward or did that do more harm, or is it a mix?

A: The truth is I don’t know for sure what the impact was on the official channel. As you can imagine, we’re not the government. The government doesn’t share the information. We coordinate and we share with them. It’s typically more of a one-way street and it is very unusual to go in a public way the United States did. I hope it was successful for them. As Governor Richardson says, sometimes when you think things are stuck, you need to release a bomb into the negotiation to shake things up. He attributes what the U.S. did to that, and look, it did shake in the fact that Lavrov responded to that and the two sides are now talking. Does that hurt or harm the ability to actually complete the negotiations? I prefer the negotiations happen quietly even if for one reason: There’s a lot of people who would not want this deal to happen. There’s a lot of people who will be against it. When you broadcast what the deal is before it happens, you’re giving them an opportunity to spoil. One of the reasons why we try to do all these quietly is that by the time it’s public, it’s done, and you can get all the criticism, but the Americans are back home.

Q: Ambassador Richardson said just a day or so ago that he thinks this is going to be a two-for-two deal, not a two-for-one as many envision. What leads him to that assessment?

A: First of all, I have to say that that comment is not based on inside information that we’re providing. This is just based on our experience, especially working with the Russians. The Russians, as well as the Iranians, in past dealings that we’ve had with them do want to have symmetry, even for the public eye. So sometimes, doing a one-for-two is a starting negotiating position, but in all likelihood, in our experience, this will end up in a symmetric approach of a two-for-two. It’s not symmetric in terms of justice, obviously, but it’s symmetric in terms of numbers. Who the second person might be, it’s up to negotiations. I know the Russians have raised some names. The Americans might have things in their mind.

Q: How are the Griner and the Whelan families holding up under all this?

A: I actually spoke to both families today, separately, just on our updates. Look, it’s hard for anybody who’s not experienced it to imagine the pain that is happening. It’s not only that your loved one is stuck in the conditions that they’re stuck in. It’s that feeling of helplessness. And they’re doing everything they can. Each family is in an impossible situation because they have real partial information and misinformation. A lot of people come to them with things and they need to make decisions and every decision they make might be the decision that will bring their loved one home or might make their loved one suffer and they don’t have the information. So, it’s an impossible situation for all of them. They handle it differently. There are organizations that try to support them. The U.S. government has some tools to try to support them. But it is torturous. And these cases, as we’ve seen them typically, they’re about 20 cases on average at any given time. We are facing about 70. Now, that is a huge number. It’s a national crisis. I think the president two or three weeks ago made an executive order that actually referred to it as a national crisis. Hopefully, that will be a step forward in trying to look at an all-of-government approach to actually put some deterrence policies behind it and make sure that we mitigate this problem because otherwise this keeps coming up. Look at Venezuela: About 13 Americans are being held. Iran has four. Russia has two public and a few more. China has a bunch of them. These are the serial offenders. Then we have individual countries. We have single cases as well.

Q: You said there’s no such thing as a prisoner released for free, but you told me earlier that Danny Fenster was released without anything in return. So, what was really given in return there?

A: It’s interesting because it touches on how we approach things. We will often look at negotiations as a zero-sum or transactional thing, a give-and-take. In Hebrew, ten v’kach. In the case of Danny Fenster, we approached it from a very relationship-based approach. We believe that negotiations are our ability to influence somebody else’s behavior. In the case of Danny Fenster, yes, we did give something back. That something was a photo op, almost, with the head of the military government in Myanmar. Having somebody of the stature of Governor Richardson show up; have good, positive meanings; develop a good relationship between them—it doesn’t mean that we will legitimize any of the actions that they take … we’re not the government. We don’t have the power to legitimize anybody. But it is symbolic because Governor Richardson, as well as myself, has been very involved in Myanmar over the years. That’s part of the relationship. So yes, there is an argument there that we gave them a little bit of legitimacy through a photo opportunity. I would argue that if that’s what we need to give in order to save Danny Fenster’s life, I’ll do it any day.