By Gordon Atlas

Gordon Atlas, Ph.D., taught at Alfred University and is now, like all good Jews, retired to Florida. When he was teaching at Union College in Schenectady in the 1980s, Atlas and Jewish World publisher Jim Clevenson, who had studied philosophy together in Binghamton, shared coffee and stronger drinks while investigating the Self, leather-jacketed nightlife, and the Grateful Dead. His book Inside Humor explores one of our cherished human abilities and characteristics.

Look who’s laughing!

The perception that has been prominent in my courses on comedy—that the type of humor a person engages in fits his personality— could be enriched by a language and an understanding of how that makes sense. In my experience, humor is one of the most diagnostic elements of personality—but we have been largely unable to bring that intuition into the realm of substantive knowledge. This book suggests a structure that will enable such studies.

The present work explores the possibility of a hierarchy of humor, in the context of understanding the various forms of humor and what humor really is. The central question is: What is humor?

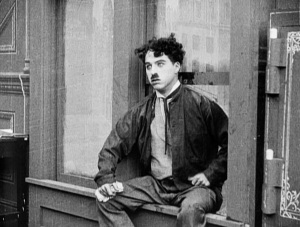

Charlie Chaplin: The New Janitor

Charlie Chaplin in ‘The New Janitor,’ 1914: We identify with innocence

In The New Janitor (Sennett & Chaplin, 1914), Charlie Chaplin plays a physical laborer who is wielding a broom that he is on the verge of losing control of. He is a menial worker in a business with administrators carrying out their executive plans. As he marches down the hall, he unintentionally swings the broom back and forth, hitting an executive in the head. This stuns the executive, of course, but even further—as he begins to recover, Chaplin delivers another unintentional blow in his own effort to control the broom. In the simplest terms, this scene could be regarded as unfortunate or even tragic in that it results in injury to an innocent party.

But the incident is funny. Why? Because of the relationship between the menial worker (Chaplin) and the executive. But let us begin again with the hero, the Chaplin character. The audience must, first, be convinced that Chaplin—as the menial laborer—is of a pristine consciousness. He has no ulterior motives. He is completely innocent, simply trying to make a living but rather awkward and maybe a bit pitiable. His movements, however, are somehow both awkward but also fluid. He swings back and forth easily but without control. If we find this funny, it is because of our identification with the innocence of the Chaplin character.

Imitation As Humor

Another rather immediate and direct form of humor is that of “imitation.” During recess on the school grounds, a talented student impressionist imitates their stuffy, difficult teacher as the other students roll on the ground with laughter. A young child tries to speak “adult talk,” and it is so funny that a YouTube video goes “viral”–and everyone must see this little kid acting as an adult. Parents get together and tell stories of their children’s antics, imitating the voices of their 4-year-olds, which leads to more stories and chuckles.

Why is imitation such a powerful form of humor? According to Duffy and Teruggi (2013), the use of imitation humor (through late-night comedy shows such as Saturday Night Live or The Late Show with Stephen Colbert) has become even more prominent than ever. The proliferation of such shows speaks to that observation quite clearly. If President Trump (or now, Biden) issues a statement about immigration, it is hardly humorous—but when that same statement is mocked by Alec Baldwin on Saturday Night Live, it cracks us up. Impersonations, such as those by Frank Caliendo of George W. Bush, are funny because they capture the idiosyncrasies of the targeted person.

Frank Caliendo (2006) begins his impersonation of George W. Bush by saying, “He is the only person I know that looks like he’s always looking at the sun.” He then does the Bush squint in a perfectly imitative fashion. “Can somebody do me a favor and hand me a pair of sunglasses?” His dumbing-down of George W. is very engaging. The audience can’t get enough of it.

Observational Humor

Observational Humor

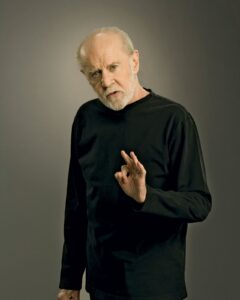

“Do you ever get lip crud? That crud on your lip? It’s kind of a sticky film, a gooey coating? You know, if it dries a bit, it’s kind of a gummy, cruddy, flaky, crusty kind of thing. It starts in the corner of your mouth and works its way down your lip. And if it’s really bad, the corners of your mouth look like parentheses? Do you ever have that?” (Carlin, 2001)

This is an excerpt from a George Carlin routine that is focused on weird stuff about our bodies that we never talk about. This form of humor is striking because it is difficult to determine what the “comic” aspect is. There does not seem to be a punchline; there is no contrast that is pointed out, no narrative, and no political commentary. Many of the aspects we see in other forms of humor are strikingly absent from observational humor. Upon reflection, it is clear that the simple “observation” is precisely what is humorous. But what does this “observation” accomplish for us? How is it funny to point out small details of life?

One beginning point here is to examine the contrast between public and private life that this form of humor highlights. Lip crud is something everyone has noticed but has probably never discussed in public. The comic violates that unwritten rule that you do not talk about private matters and bodily functions in a public setting. The private, therefore, becomes public. There is a sheepish, revelatory laughter that this form of humor triggers. Laughter ensues at the recognition of the way this private aspect of life is readily recognizable, able to be articulated, and can be shared with others, while a taboo exists against its being publicly discussed.

Sarcasm and Satire

The real estate broker shows a young couple a house that has been on the market for some time. As they enter the house, the smell of mold is overwhelming, dead insects are scattered across the linoleum, and the floors creak as they walk on them. “We’ve found our dream house!” exclaims the husband. (fictional narrative)

Sarcasm, as a form of humor, has received little research attention. Freud in 1905 saw sarcasm as a manifestation of unconscious aggression. This is a difficult point to argue—for or against. Philosophical critics of Freud, like Grunbaum (1984), would probably argue that this is, at best, speculative and not falsifiable because it resorts to the existence of an unseen entity—the unconscious. But the question of causality can be debated endlessly, and is not the concern here. Our task is to enter the experience of sarcasm —the question is “What is the sarcastic person accomplishing in the moment of his sarcasm?”

On the Hilariously Funny….

More typically, what is most funny to people are personal experiences that involve a narrative that develops into an inside story that has a personal meaning. Most will nominate experiences such as when a friend made a fool of himself in front of someone he was trying to impress, or a silly thought that occurred during church that they shared with a friend, which led to their being unable to control their laughter, despite the serious sermon being delivered. Often a visual image will be at the center of this comedic experience, as in, “I keep thinking about the time when my brother dropped the groceries all over the street.” The hilariously funny is almost always of this character, and the laughter one experiences is uncontrollable and overwhelming. “Whenever I think about Mr. Simpson lecturing the class while Johnny was mooning in the corner, I can’t help but crack up.” (Please excuse the pun!)

What is the nature of the hilariously funny, though? Why is it that personal situations are almost always recognized as the most profoundly comedic? What is the role of the visual image in these cases? How does the social sharing of these experiences become so prominent that they become central to powerful social relationships?

Is there a qualitative difference between this category of the hilariously funny and the simply funny? It appears that this is the case. One can attend a comedy club performance and find much of the material to be extremely funny. A sitcom can produce many comedic moments—even ones that are discussed with friends: “Do you remember the time that George, on Seinfeld, quit his job, then thought better of it, so he returned to work and pretended that nothing happened? That was hilarious!” At a dinner party, another couple may relate their funny stories, and one may be compelled to retell those stories to other friends and marvel at how funny they are. Some well-told jokes are worthy of being told and retold and promote uproarious laughter time and time again.

But the really hilariously funny rarely comes from one of those domains and, instead, nearly always originates from one’s private experience. The “inside joke” or “family joke” is one form in which this may arise. They are situational, private, and much of the humor may lie in the personalities and idiosyncrasies of the people involved. You had to know Mr. Simpson—how stern he was and how he tortured the class all semester about not being serious enough—to appreciate how funny the gesture of this student was. We often say, “You had to be there!”

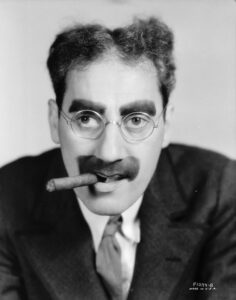

Groucho Marx (1890 – 1977) circa 1935, with his trademark mustache and glasses. (John Kobal Foundation—Getty Images): Playing with grammar

Discrepancy Humor

Groucho Marx, about his experience on an African safari: “One morning, I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas, I’ll never know.” (Marx, 2021)

The incongruity here lies in the change in image that is inspired by the surprise twist in the story. As we read the first part, it is perfectly clear that he means he was wearing pajamas while he shot an elephant, assumed to be in the distance (or at least a few feet away!). The phrase “in my pajamas” is allowed, in the second part, to be literal. Now we are forced to consider an elephant that is actually in Groucho’s pajamas—a very different situation altogether and one that is humorous in itself. But the brilliance of this story is, of course, in the switch—and the fact that we cannot deny that the second articulation is, in fact, literal and correct, grammatically and semantically.

Irony

A husband and wife who loved to play golf were driving home one night and ran into a bridge abutment, and both were killed. They arrived in heaven and found it was a beautiful golf course with a lovely clubhouse and fabulous greens. It was free and only for them, and the husband said, “You want to play a round?”

She said, “Sure.” They teed off on the first hole, and she notices that the husband is upset at something. “What’s wrong?” she asks.

“You know, if it hadn’t been for your stupid oat bran, we could have been here YEARS ago!” (Keillor, 2003, p. 88)

This is a clear case of irony. What the husband and wife strove for (living a healthy life that would lead to longevity) turned out to prevent them from obtaining what they really wanted. It was precisely that which they did to avoid the negative (eat lots of oat bran) that led to their not reaching their goal (beauty, happiness, freedom) as soon as possible. But there is more than common irony in this story. The story illustrates that one can induce his own circumstances by his own actions. This is deep irony—not just happenstance.

Wisdom Humor

Mulla Nasrudin’s face lit up as he recognized the man who was walking ahead of him down the subway stairs. He slapped the man heartily on the back and cried, “Goldberg, I hardly recognized you! Why, you have gained thirty pounds since I saw you last. And you have had your nose fixed, and I swear that you are about a foot taller.”

The man looked at him angrily. “I beg your pardon,” he said in icy tones, “but I do not happen to be Goldberg.”

“Aha!” said Mulla Nasrudin, “so you have even changed your name!” (Suresha, 2014)

The second aspect of wisdom outlined by Kross and Grossman harkens back to Socrates’ notion of knowing one’s own limits as far as knowledge goes. The fool assumes too much; the wise person recognizes that we, as humans, can only know so much and is more cautious and prudent. In this Mulla Nasrudin tale, the person refuses to recognize his own limitations and insists that his first perception—that this is his friend, Goldberg—is correct, even when the evidence mounts that this is not the case. The humor lies in Mulla’s foolishness in the face of the obvious. Recognizing one’s own limitations is crucial to the process of developing wisdom.

More on Wisdom Humor

There once was a teacher who lived with a great number of students in a run-down temple. The students supported themselves by begging for food in the bustling streets of a nearby town. Some of the students grumbled about their humble living conditions. In response, the old master said one day, “We must repair the walls of this temple. Since we occupy ourselves with study and meditation, there is no time to earn the money we will need. I have thought of a simple solution.”

All the students eagerly gathered closer to hear the words of their teacher. The master said, “Each of you must go into the town and steal goods that can be sold for money. In this way, we will be able to do the good work of repairing our temple.”

The students were startled at this suggestion from their wise master. But since they respected him greatly, they assumed he must have good judgment and did not protest.

The wise master said sternly, “In order not to defile our excellent reputation by committing illegal and immoral acts, please be certain to steal when no one is looking. I do not want anyone to be caught.”

When the teacher walked away, the students discussed the plan amongst themselves. “It is wrong to steal,” said one. “Why has our wise master asked us to do this?”

Another retorted, “It will allow us to build our temple, which is a good result.”

They all agreed that their teacher was wise and just and must have a sensible reason for making such an unusual request. They set out eagerly for the town, promising each other that they would not disgrace their school by getting caught. “Be careful,” they called to one another. “Do not let anyone see you stealing.”

All the students except one young boy set forth. The wise master approached him and asked, “Why do you stay behind?”

The boy responded, “I cannot follow your instructions to steal where no one will see me. Wherever I go, I am always there watching. My own eyes will see me steal.”

The wise master tearfully embraced the boy. “I was just testing the integrity of my students,” he said. “You are the only one who has passed the test.” The boy went on to become a great teacher himself. (Khan, 1939)

There are several morals to this Jataka tale, which probably dates from the 4th century B.C. One of the themes has been prominently studied in modern social psychology—that of obedience. The students who carried out the master’s orders did so with blind obedience, even though they had serious reservations about committing the transgressions. Perhaps this serves as an ancient example of obedience to authority, which was demonstrated so powerfully in the Milgram experiment (Milgram, 1963) in which subjects were willing to give electric shocks at an alarming level to peers in the experiment. Of course, the Milgram study was “rigged” with a confederate playing the role of another subject and no real shock was imposed. The wise student here is heroic in that he thinks for himself and is unwilling to carry out the unethical commands of the master.

But the notion of “seeing oneself” is critical in this tale. The master exhorts his students to “not be seen” as they commit these acts, knowing full well that this is impossible. The student’s task is to recognize this impossibility, but only one student realizes this. Wisdom lies in this inability to carry out the master’s orders, but also in the master’s strategy, as it provides an excellent test of the students’ discernment.

What is the humor here, though? Remember that wisdom humor is, generally, not going to engender a deep belly laugh or a loud outburst but, rather, an “aha” chuckle, and this tale certainly can produce this sort of reaction. We’re laughing at the twist in the story—that this was a test given by the master that only the wisest student could pass. We’re also acknowledging the truth of the good student’s response, “One sees oneself at every moment.” And perhaps we’re laughing at the unexpected reversal involved in the correct response to the master’s command being defiance or refusal.

Humor Is Indefinable

Ultimately, humor is not definable. Our understanding of humor as “transcendence” is most universal but not satisfactory. Humor is sometimes said to be the perception of incongruity that leads to laughter. But many other emotions may result from the perception of incongruity. A person might be bewildered, angry, surprised, disconcerted, or confused. The addition of laughter is “cheating,” because that implies humor in the definition.

To define humor, we would have to refer to something that is not humor but which somehow is akin to or related to humor. To define humor, we would need other words for the concept of humor. But there is simply nothing like humor. We can say a great deal about it, but we cannot really define it in terms other than itself.

Consider a person who is completely humorless. I don’t mean your boss or a person whose sense of humor is limited or primitive or weak—but one who has no access to humor whatsoever. How could you explain what humor is, such that they would be able to engage in it? It would be impossible. You could point to incongruities, ironies, surprise endings, or even resort to tickling them—but to no end. Humor cannot be arrived at from outside of it.